Why we need to protect New England’s ocean treasure

The miracle of the ocean is that it fills us with wonder, even as most of it remains undiscovered.

Our ocean’s unfolding tragedy is one of human activity and its consequences. Rising temperatures, increasing pollution, and overharvesting by large-scale fishing threaten to rob us and the ocean of that very wonder. In 2018, scientists found that only 13% of the world’s oceans could be considered “wilderness,” or untouched by people.

There’s much work to be done to halt and repair this damage, but one of the most consequential tasks is also one of the simplest: We can protect and conserve some of the last truly wild places in our ocean.

Places like Cashes Ledge.

Cashes Ledge–A kelp forest wonderland

Cashes Ledge is a wonderland of kelp fronds waving in the current, where cod and crabs hide. Craggy underwater mountains plummet to sandy plains while predators such as sharks hunt among the blades of kelp, cracks and crevices, sand flats and water column. The tallest underwater peak, Ammen Rock, stands about 90 miles off the Massachusetts coast in the center of the Gulf of Maine mountain range. Just like a terrestrial national park, this incredible geological feature creates a unique “mosaic” of habitats.

On Ammen Rock sits the deepest, densest and healthiest kelp forest in the Gulf of Maine and possibly the Northwest Atlantic, a veritable “oasis” for fish. Cliff faces dropping into the deep Gulf host a kaleidoscope of yellow, red and rare blue sponges. In the water column, life adapted to different temperatures and conditions thrive, fed by currents and abundant kelp. The area’s steep cliffs form internal waves that circulate nutrient-rich water and send kelp remnants throughout the ecosystem.

This region is a hotspot for marine mammals, including humpback, minke, and fin whales that flock to the rich feeding grounds. But they’re not the only animals traveling from afar: Cashes Ledge is wintering ground for Atlantic puffins, listed as vulnerable by the IUCN. These birds fly long distances searching for food–and this kelp forest is home to plenty.

However, the most famous Cashes Ledge resident is the Atlantic cod. Cashes Ledge is one of the last and best places to find the fish, which remains overfished in the Gulf of Maine following a massive collapse in the late 20th century. In contrast to the greater Gulf, Cashes Ledge is home to big, healthy cod: fish up to three feet long have been found within Ammen Rock’s relatively shallow kelp forest, and up to five-foot long “whale cod” have also been observed on Cashes Ledge’s northern edge.This diversity of habitats and species, as well as their beauty, led ocean explorer and marine scientist Sylvia Earle to call Cashes Ledge the “Yellowstone of the Atlantic.”

See this video about Cashes Ledge presented by the Conservation Law Foundation and New England Ocean Odyssey.

New England’s ocean at risk

Right now, the Gulf of Maine faces the same problems as the rest of our ocean. In New England alone, 15 of the 28 fish stocks caught by commercial fishermen are overfished. Decades after the fishery collapsed, populations of Atlantic cod in the Gulf remain a fraction of what they once were. Whales face fishing gear entanglement, boat strikes and rising marine noise levels. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 96 percent of the world’s oceans, adding even more stress to New England’s marine ecosystems.

We can reduce this stress by preserving hotspots for ocean life. Just like with national parks on land, ocean regions off-limits to human impact allow their species, from vibrant fish to sedentary sponges, to safely survive and thrive.

But today, none of the Gulf’s most important and biodiverse ecosystems are permanently protected from destructive human activities. If we want to restore this once-thriving ocean, we must save its last remaining healthy areas.

The Yellowstone of the Atlantic is at risk

Right now, this area is the closest we have to the ocean ecosystems of centuries past–but it could all be at risk.

The area around Cashes Ledge has enjoyed some protections from commercial fishing over the last 20 years, largely to help recover the cod population and support other commercially caught fish. But these measures are incomplete–they’re meant to conserve a few key species but not the whales, seabirds and sponges that depend on the region. That means protections could be changed or revoked without considering impacts on non-fished inhabitants. Furthermore, the protections aren’t permanent–a simple rule change by fishery managers could remove them at any time.

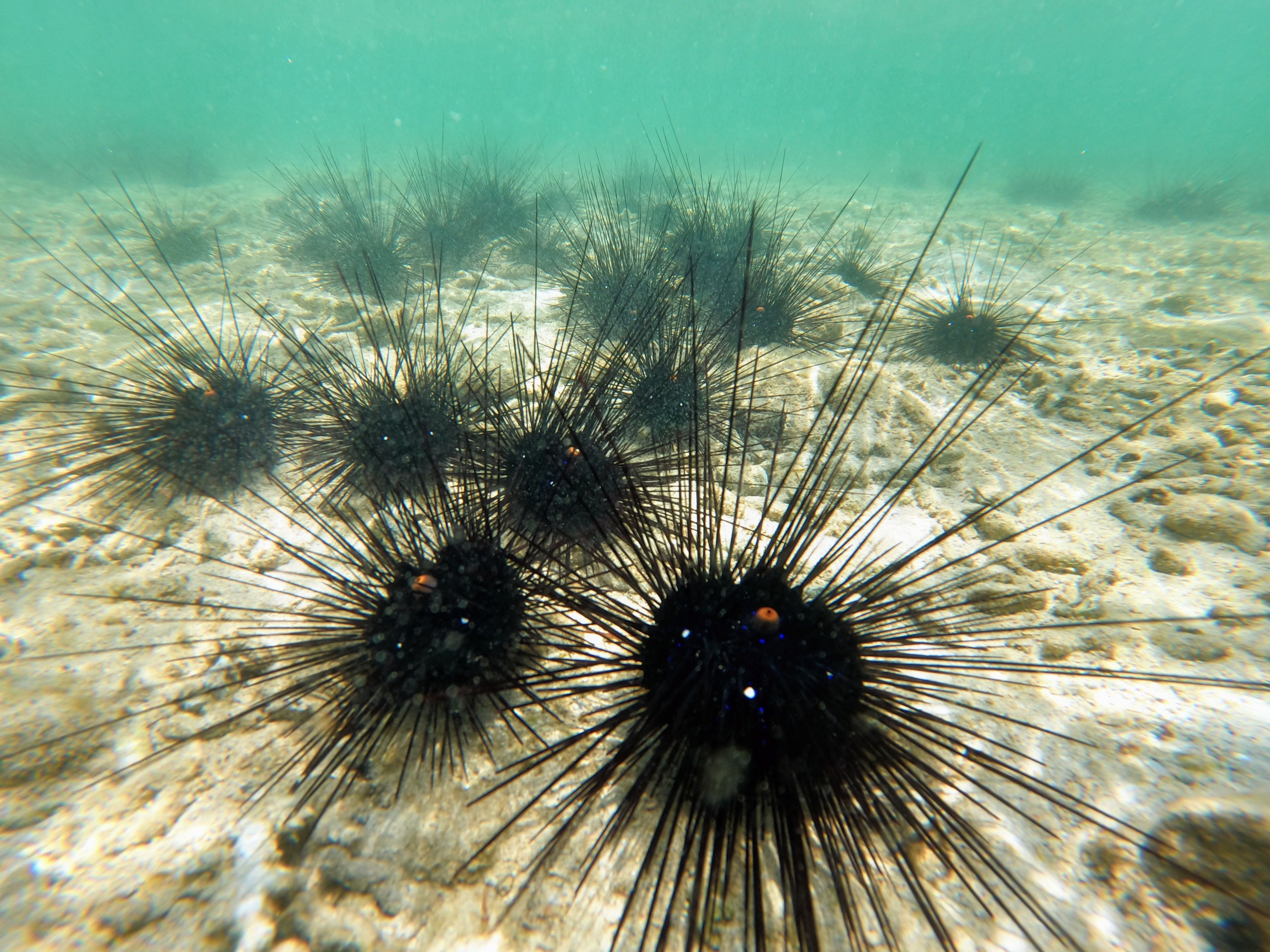

What’s more, the fact that cod and other large fish remain at Cashes Ledge likely plays an important role in keeping the kelp forest healthy: at places like Cashes Ledge, cod and other fish have historically been key predators in regulating sea urchins, letting the kelp thrive by preventing the urchins from overgrazing–mowing down kelp forests like cattle grazing in a field.

We can’t risk disrupting this wild place. We need to permanently protect Cashes Ledge.

Preserving an oasis for life in the North Atlantic

From Yosemite National Park to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Environment America has a storied history of recognizing the need to preserve truly wild places. While only a fortunate few of us will ever see Cashes Ledge in person, we can still appreciate the amazing plant and animal life filling its waters. Permanently protecting its kelp forest and surrounding ecosystems will be a great step towards preserving the beauty and abundance once found throughout the Gulf of Maine. It will help our whales feed, our seabirds soar and our cod recover. It will be a crucial investment in the future our ocean needs.

Join us in calling on President Biden to permanently protect the amazing ecosystem around Cashes Ledge.

Topics

Authors

Kelsey Lamp

Director, Protect Our Oceans Campaign, Environment America Research & Policy Center

Kelsey directs Environment America's national campaigns to protect our oceans. Kelsey lives in Boston, where she enjoys cooking, reading and exploring the city.

Steve Blackledge

Senior Director, Conservation America Campaign, Environment America Research & Policy Center

Started on staff: 1991 B.A., Wartburg College Steve directs Environment America’s efforts to protect our public lands and waters and the species that depend on them. He led our successful campaign to win full and permanent funding for our nation’s best conservation and recreation program, the Land and Water Conservation Fund. He previously oversaw U.S. PIRG’s public health campaigns. Steve lives in Sacramento, California, with his family, where he enjoys biking and exploring Northern California.

Find Out More

A wave of youth ocean activism in Boston

Let’s protect Oregon’s underwater forests

Save the Whales