As the rate of climate-fueled natural disasters, extreme weather and species extinctions increase, environmental activists and scientists have grown all the more intent on finding ways to curb greenhouse gas emissions, which are the primary cause of climate change. Greenhouse gases trap heat inside the Earth’s atmosphere much in the same way a traditional greenhouse does, heating up the atmosphere and changing the climate. In 2019, carbon dioxide made up about 80% of greenhouse gas emissions. Other greenhouse gases, such as nitrous oxide, methane and fluorinated gases, also pose a major threat to the atmosphere.

While we know the dangers greenhouse gases present, one issue has been determining how we measure them. More than 20 years ago, in 2001, the World Resources Instituteand the World Business Council for Sustainable Development collaborated to create the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol), which acts as an international set of emissions guidelines for public and private entities.

Companies can use the GHG Protocol as a method of tracking and reporting their emissions. The protocol allows cities, companies and other groups to reach measurable emissions goals and standards such as those agreed on when nations signed the Paris Agreement.

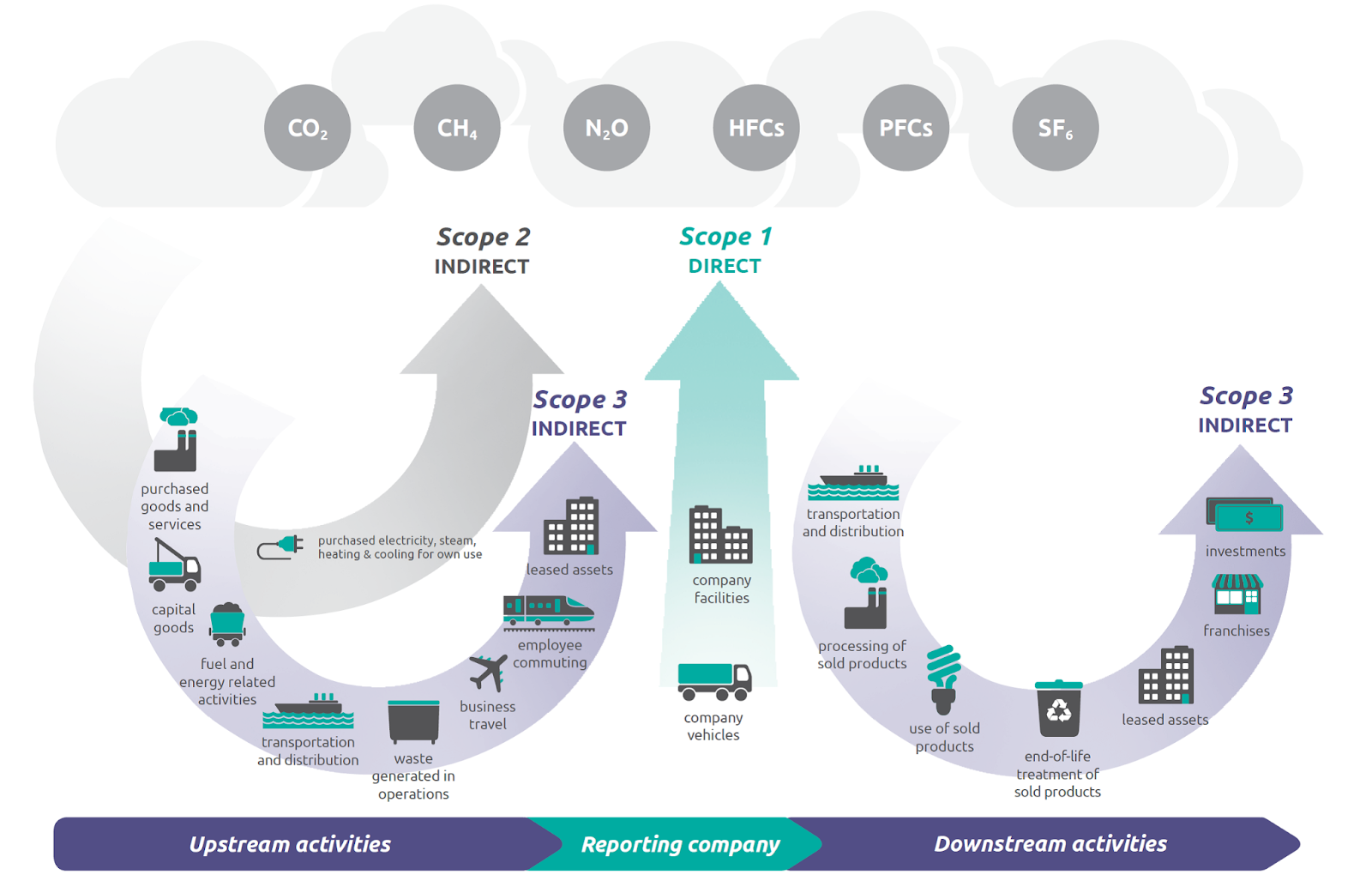

The GHG Protocol divides greenhouse gas emission into three scopes based on how they’re created.

-

The first scope, known as scope 1, accounts for the emissions that a company creates directly, like emissions from fuel combustion to run machines that create products and engines that power company vehicles.

-

The second scope (scope 2) covers emissions that the company doesn’t create directly, but uses, such as electricity and heating.

-

The scope 3 emissions category includes all of the other emissions released throughout a company’s value chain, which refers to the process of taking raw materials and manufacturing them into a product. Basically, scope 3 emissions cover all of the emissions a company is associated with but isn’t necessarily directly responsible for. This category of emissions is divided into upstream and downstream activities. The upstream group encompasses emissions from the supplier side of the business, such as travel, purchase of goods and services, transportation and distribution. This category also includes capital goods such as buildings and machinery. Downstream focuses on emissions that are created once the product makes it to the consumer. This includes investments, franchises, uses of sold products and disposal of sold products.

Image credit: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

While companies discuss and disclose scope 1 and 2 emissions, they often ignore scope 3. This is especially problematic because scope 3 emissions have the greatest impact on the climate. If we want to reduce our carbon output and slow climate change as a society, scope 3 emissions must be a part of the conversation.

For example, the emissions caused by logging a tree, transporting it to a pulp mill, operating the mill to turn the tree into wood pulp, and transferring the wood pulp to a manufacturing plant are all upstream scope 3 emissions. The greenhouse gases caused by operating the manufacturing plant to make a box of tissues are Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The emissions created by a consumer driving to a store to buy the tissues, then throwing the used tissues away so that they eventually release carbon in a landfill are downstream scope 3 emissions.

Scope 3 emissions often account for the vast majority of a company’s carbon footprint, sometimes reaching percentages as high as 85% or 90% of total emissions. This number is especially high for companies that outsource certain aspects of their business, such as logging or product manufacturing.

While the Environmental Protection Agency requires large emitters to report scope 1 and scope 2 emissions, they are not required to report scope 3 emissions, and rarely do so voluntarily. While it is understandably challenging to track all scope 3 emissions, avoiding doing so is detrimental to any real attempt to reduce emissions.

By failing to account for scope 3 emissions, a business could reach net zero emissions goals by addressing scope 1 and 2 activities and market itself as a green company – all while completely ignoring the majority of its carbon footprint. Despite this clear loophole, the idea of requiring companies to report on their scope 3 emissions remains highly contentious.

The problem, according to companies, is that scope 3 emissions are difficult or even impossible to tabulate. In order to successfully reduce scope 3 emissions, companies need access to information surrounding their supply chains and data to create science based targets. This information has been lacking, possibly because there is little incentive for companies to put effort into streamlining the data gathering process. But it’s not impossible. According to Ceres, a nonprofit that promotes market-based solutions to climate change, more than 3,000 companies have reported their scope 3 emissions. It can be done.

Without a focus on scope 3 emissions, the world faces a significant barrier to mitigating climate risk. These emissions present the greatest opportunity to make an impact on our carbon emissions. Without including all types of carbon output in a company’s value chain, other efforts to regulate or report emissions end up being more performative than impactful. So, for the sake of our planet and all of its inhabitants, it’s time for companies to start taking the initiative to voluntarily count their scope 3 emissions.

This blog was co-authored by Environment America intern Abby Vander Graaff