Get the Lead Out

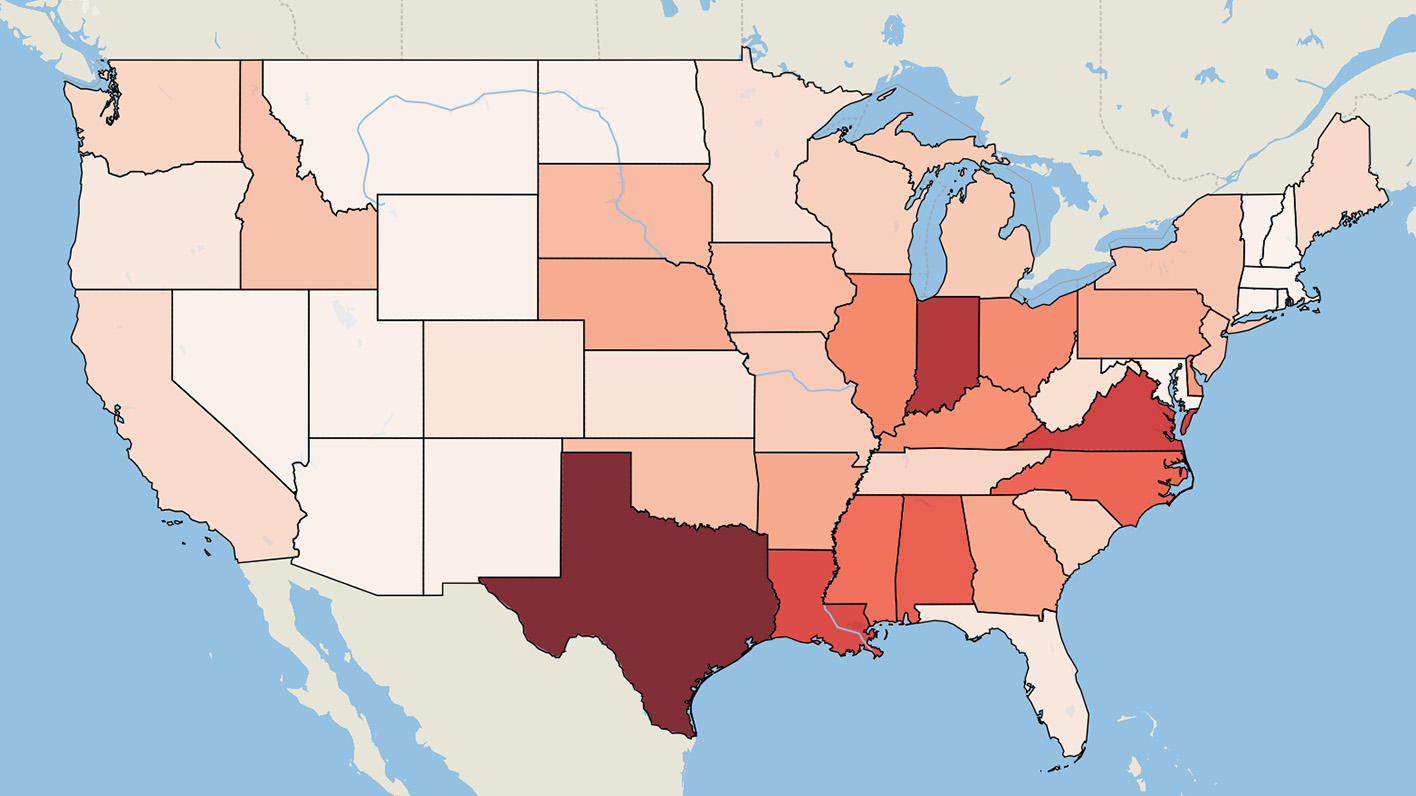

Grading the states on protecting kids’ drinking water at school

Downloads

The health threat of lead in schools’ water deserves immediate attention from policymakers for two reasons. First, lead is highly toxic and especially damaging to children — impairing how they learn, grow and behave. Second, current policies on lead in water at school are still too weak to protect our children’s health.

Explore the map and data below for our latest assessment of laws and regulations pertaining to lead contamination of schools’ drinking water — including a review of policies (or lack thereof) in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Hover over each state to see their grade and click on a state to reveal a narrative.

Washington, D.C.: B+ 143/200

Dig into more details on how we graded the states in the Methodology section below.

A threat to children’s health

Even at low levels, lead damages how kids learn, grow, and behave. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “In children, low levels of [lead] exposure have been linked to damage to the central and peripheral nervous system, learning disabilities, shorter stature, impaired hearing, and impaired formation and function of blood cells.”1 Several studies link low lead levels with learning loss in children.2 In light of this alarming data, public health experts and agencies now agree: There is no safe level of lead for our children.3

Lead damages kids' brains, promotes ADHD and shaves off IQ points. There is no safe amount.Ron Saff, M.D.

Assistant clinical professor of medicine at the Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee

Contaminated water at schools

Most schools have at least some lead in their pipes, plumbing or fixtures. And so, as more schools test their water, they are finding widespread lead contamination. Moreover, lead concentrations in water are so highly variable that even proper testing can fail to detect it. So in all likelihood, the confirmed cases of lead in schools’ water — as we’ve documented in our interactive map — are just the tip of the iceberg.

Ensuring safe drinking water at school

Instead of only fixing taps where highly variable tests confirm the presence of lead, state policies should require steps to prevent contamination at every school outlet used for drinking water or cooking, including:

- Replace fountains with water stations that have filters certified to remove lead;

- Install, test and maintain filters certified to remove lead on all taps used for drinking or cooking;

- Set policies to ensure that schools are no longer using plumbing and fixtures that leach lead into water;

- Adopt a 1 ppb limit for lead in schools’ drinking water, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics;

- Fully replace all lead service lines, which are relatively rare at larger schools but more common at child care centers.

For all schools and child care centers that are federally regulated as public water systems, the EPA should at least require replacement of lead service lines, installation of filtered water stations (to replace fountains) and filters at all drinking water and cooking taps.

Yet concerned parents need not wait for state or federal action. Several school districts are acting on their own to stop lead contamination of their water. See our toolkit to find out how you can work with your local school to get the lead out.

Methodology

In grading states’ policies to prevent lead in schools’ drinking water, we first assigned points for specific measures based on our assessment of their relative importance in ensuring lead-free water at school:

After scoring each state’s policies, we then assigned a grade for each state using the following rubric:

A few notes on our grading methodology

First, while we mostly assessed enforceable laws and regulations, we also sought to award limited, partial credit to states for voluntary programs with demonstrated results. Massachusetts, for example, has tested more than 50,000 taps at 1,000 schools, urges remediation to the lowest level possible, and has committed funding to help schools replace fountains with filtered water stations. But voluntary efforts only go so far. Without any enforceable law or regulation to protect children’s water at school, the Bay State only earned a C-.

Second, while our analysis graded policies applicable to schools, we gave additional credit to states with rules to stop lead contamination at early childhood programs. As per a previous study by the Environmental Law Institute, some states have requirements that apply solely to child care facilities. We did not grade states on the strength of those separate child care policies in this report.

Third, in several instances, a state policy only partially met one of our criteria. In some cases, assigning points for these policies was relatively straightforward; for example, a state law that applies to all schools but no child care facilities earned 10 out of 20 potential points. But a law that only applies to public schools k-6, or only to publicly-run early childhood programs but not private daycares? We just had to use our best judgment and strive to be consistent with all states.

Fourth, while lead service lines are relatively uncommon at schools, they are the most significant source of lead-water contamination in other places where children live, learn and play – including child care facilities. Accordingly, our scoring awarded bonus points to states making substantial efforts to replace these toxic pipes that go beyond using dedicated federal funding. Only New Jersey received the full 30 bonus points for the strongest policy, which requires full replacement of lead service lines with a 10 year deadline.

Fifth, based on more data and enhanced information on effective solutions since 2019, we adjusted some of the point values we assigned for certain policies since our last report. As a consequence, a few states now have a slightly different grade even if they have made no change in policy since 2019. Conversely, a few states that have improved their policies did not see their point scores increase as much as they would have under our previous scoring. A few states have also issued new clarifications or guidance of existing policies since 2019, and we adjusted our point scores for those as well.

Finally, to some degree, the successful implementation of lead prevention policies will depend on funding and enforcement. Yet funding comes from so many different sources — including the federal drinking water state revolving fund — that we could not establish a reliable way to assess sufficient funding for any given state’s efforts. Similarly, absent uniform data, we had no meaningful way to compare the effectiveness of state enforcement or compliance efforts.

Sources

Alaska

- Alaska has no state laws or regulatory requirements to address lead in schools’ drinking water. See e.g., [LINK]

Arizona

- ADEQ, “Public School Drinking Water Lead Screening Program Corrective Action Guidance.” Accessed March 6th 2019 at [LINK]

- Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, “Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Public School Lead Drinking Water Screening Program Sampling Plan & Collection Log for Experienced Sample Collectors.” Accessed March 6th 2019 at [LINK]

- ADEQ presentation on testing (showing some taps capped or signage posted), at [LINK]

- ADEQ Lead in Drinking Water Results. available at [LINK]

Arkansas

- Lead Testing in School and Child Care Program Drinking Water Grant – Work Plan for the State of Arkansas, accessed Feb 3, 2023 at [LINK]

California

- California Water Boards, “SAMPLING GUIDANCE: Collecting Drinking Water Samples for Lead Testing At K-12 Schools,” December, 8 2017. at [LINK]

- Cal. Health & Safety Code § 116876, added by Stats.2021, c. 692 (A.B.100), s1, eff. Jan. 1, 2022

[LINK] - Lead Service Lines: An act to add Section 116885 to the Health and Safety Code, relating to drinking water, SB 1398. September 27th 2016. Cal. Health & Safety Code § 116885

Available at [LINK] - Health and Safety Code: Pure and Safe Drinking Water, Article 1 added by Stats. 1995, Ch. 415, Sec. 6. Cal. Health & Safety Code § D. 104, Pt. 12, Ch. 4, art. 1.

[LINK]. - California Water Board, “Lead Sampling of Drinking Water,” February 15th, 2019. Available at [LINK]

- California Water Board, “Lead Service Line Inventory Requirement for Public Water Systems,” February 14th, 2019. Available at [LINK]

Colorado

- Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 25-8-903 [LINK]

- CDPHE, Test and Fix Water for Kids [LINK] accessed Jan 27, 2023

Delaware

- Delaware Dept of Education, Drinking Water Sampling at Delaware Schools, at [LINK] and Letter to Parents, both accessed from the State of Delaware’s Safe School Drinking Water webpage, at [LINK]

- State of Delaware, 2023 Lead in Drinking Water Sampling Dashboard, accessed at [LINK]

- Cris Barrish, Momentum builds to install filtered water stations in all Delaware schools to ‘get the lead out, WHYY, Feb 1, 2023 at [LINK]

District of Columbia

- § 38–825.01a. Prevention of lead in drinking water in schools. Available at [LINK]

- DC Water, “New District Lead Service Line Replacement Program Offers Historic Opportunity To Replace Old Plumbing,” December 6th 2018. Available at [LINK]

- Department of General Services, “Water Filtration and Testing Protocol,” September 28th 2017. Available at [LINK]

- DC Water, “DC Water Service Information” Available at [LINK]

- District of Columbia Public Schools, “Early Learning” Available at [LINK]

Hawaii

- health.hawaii.gov [LINK]

- health.hawaii.gov [LINK]

- health.hawaii.gov [LINK]

- Stage 2 final report: [LINK]

- U.S. News Education (showing 210 elementary schools in Hawaii) at [LINK]

Idaho

- Idaho DEQ, Lead in Drinking Water at Schools and Child Care Facilities, accessed Feb. 3, 2023 at [LINK]

Illinois

- 225 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 320/35.5

- Illinois Department of Public Health, Lead in Water Testing at Schools and Child Care Facilities (concluding pre-2014 schools should test), available at [LINK]

- DCFS, Lead Testing of Water (for child care facilities), accessed at [LINK] See also Lead Care Illinois, Illinois Lead in Water Testing Rules accessed at [LINK]

- Lead Service Line Replacement and Notification Act, Public Law 102-0613, accessed at [LINK] See also IEC, Ill. Gov. JB Pritzker signs bill to replace toxic lead service lines, Aug. 30, 2021 at [LINK]

Indiana

- [LINK] (same as bill HEA 1265) [LINK]

- IFA Phase II of the Lead Sampling Program [LINK]

- Tom Neltner, American Water lays out a plan for replacing lead pipes in its Indiana system, EDF, Feb. 24, 2018 at [LINK]

- Sara Jerome, $177 Million Job: Replacing Indiana’s Lead Service Lines, Water Online, Aug. 7, 2018 at [LINK]

Iowa

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

Kansas

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

- Kansas Dept of Health & Env., Lead Testing in Schools & Child Care Facilities, at [LINK]

- Kansas Dept of Health & Env., Kansas Lead in Facilities Sampling Program, at [LINK]

- Ballotpedia, Public Education in Kansas, at [LINK]

Kentucky

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and KY E&E Cabinet, Voluntary Lead Testing in Schools, at [LINK]

Louisiana

- Louisiana Department of Health, “School Water testing Pilot Program.” Accessed March 6 2019 at [LINK]

- “An Act to enact R.S. 40:5.6.1, relative to safe drinking water; to authorize a pilot program for 3 drinking water testing at schools; and to provide for related matters.” HB. 632. 2018 Available at [LINK]

Maine

- Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 22, § 2604-B; LD 153 [LINK]

- A Guide to Lead Testing in Maine Schools, [LINK]

- Lead Testing in Maine K-12 Schools, [LINK]

Maryland

- Safe School Drinking Water Act (HB636), at [LINK]

- MDE, Testing for Lead in Drinking Water – Public and Nonpublic Schools: Testing Requirements and Related Documents, accessed Feb. 3, 2023 at [LINK]

Massachusetts

- MA DEP, Follow-Up Steps for Schools and EECF with Lead Detections Over 1 ppb or Copper Results Over the Action Level, at [LINK]

- MA EEA, Lead and Copper School Sampling Results, at [LINK]

- Clean Water Trust’s School Water Improvement Grant (SWIG) program at [LINK]

Michigan

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and State Lead and Copper Rule, Mich. Admin. Code R. 325.10604f(6)

Minnesota

- 2018 Minnesota Statutes, “121A.335 Lead in School Drinking Water, at [LINK]

- MN DOH and DOE, Education and Communication Toolkit: Reducing Lead in Drinking Water, at [LINK]

- MN DOH and DOE, Reducing Lead in Water – A Technical Guidance and Model Plan for MN Public Schools, at [LINK]

Mississippi

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

Missouri

Montana

- Mont. Admin. R. 37.111.832 Public Health Rule (see subsection 8)

- Montana DEQ, Lead in Schools at [LINK]

- Nicky Oullet, “Proposed Rule Would Require Lead Testing at All Montana Schools,” October 30th, 2018 available at [LINK]

New Hampshire

- N.H. Rev. Stat. § 485:17-a

- NH DES, House Bill 1421 Reduces Allowable Lead in Drinking Water at Schools and Licensed Child Care Facilities at [LINK]

- NH DES, Lead in Drinking Water Sampling Guidance, at [LINK]

New Jersey

- New Jersey Education Code, N.J.A.C. 6A:26, EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES (schools)

- N.J. Admin. Code § 3A:52-5.3 (i) 5 (child care)

- Chapter 183, AN ACT concerning the replacement of lead service lines and supplementing Title 58 of the Revised Statutes N.J. Stat. Ann. § 58:12A-40.

- NJ Dept of Health, Lead in Drinking Water at Schools and Child Care Centers (stating shut-off requirement).

New Mexico

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

New York

- Law (schools) N.Y. Pub. Health Law § 1110

- Lead FAQs for Child Care Facilities, Office of Children and Family Services accessed 1-27-23 at [LINK]

- NY Assembly, “Assembly Secures $2.5 Billion in Water Quality Improvement Funding in 2017-2018 SFY Budget” available at [LINK] ($20 million for LSL replacement)

Nebraska

- NDEE, All Nebraska schools and child care facilities eligible for free lead testing of their drinking water, [LINK]

- Ellis Wiltsey, NDEE reports on lead levels in Nebraska schools & childcare centers,

- KOLN, Feb. 7, 2022 at [LINK]

- NE Dept Health & Human Services, Lead Data and Reports, at [LINK]

Nevada

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

- U.S. EPA Region 9, U.S. EPA awards Nevada $260,000 in funding to test for lead in school drinking water, May 12, 2020, at [LINK]

- Ballotpedia, Public Education in Nevada (showing 668 schools in 2022), at [LINK]

- Nev. DEP Lead Testing Program (child care results only) [LINK]

- Angie Cradock, Early Adopters: State approaches for testing school drinking water for lead in the U.S., Harvard School of Public Health, Oct. 6, 2022, at [LINK] showing 2 taps tested per school in NV summary of 2016-18 testing, at [LINK]

North Carolina

- Law (schools): N.C. Session Law 2021-180, Section 9G.8.(a) (at 237)

- Proposed Regulation (Schools): 10A N.C. Admin. Code § 41C.1005

- Regulation (Child Care): 15A N.C. Admin. Code § 18A.2816

- Lead Poisoning Hazard (10 ppb for water): G.S. 130A-131.7(7)(g)

North Dakota

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and ND DEQ, Lead in Schools [LINK]

Ohio

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

- Ohio Facilities Construction Commission, “Lead plumbing fixture replacement assistance grants program,” January 2019. Available at [LINK]

- Ohio Dept of Health, Lead in Drinking Water (child care) [LINK]

Oklahoma

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and OK DEQ, LWSC Results, at [LINK]

Oregon

- Oregon Administrative Rules, “Reducing Lead in School Drinking Water,” available at [LINK]

- ORS, Ch. 332.334, accessed at [LINK]

- Oregon Laws 2017, Chapter 700

- Oregon Early Learning, “Preventing exposure to lead” available at [LINK]

- Multnomah County, Lead in Plumbing, at [LINK]

- Rebecca Ellis, Portland plans faster action to reduce lead in drinking water, OPB, Jan 15, 2022, at [LINK]

Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Act 39, “An act relating to the public school system” available at [LINK]

- “Governor Wolf Announces Funding to Support PWSA Lead Line Replacement,” October 17th 2018 available at [LINK]

- Morgan Lewis, Pennsylvania Paves Way to Eliminate Major Risk of Lead in Drinking Water, JDSupra, Oct. 9, 2019, at [LINK]

- Environmental Defense Fund, “Pennsylvania empowers municipalities to replace lead service lines,” December 11, 2017. Available at [LINK]

Rhode Island

- Rhode Island Department of Health, “Lead in School and Daycare Facility Drinking Water” available at [LINK]

- “An Act Relating to Water and Navigation – Lead and Copper Drinking Water Protection Act” H 8127. Enacted July 12 2016. Available at [LINK]

- Steve Ahlquist, UpriseRI, Important lead pipe replacement bill may not pass the General Assembly this session, June 22, 2022 at [LINK]

- Brent Addleman, New bill would work to eliminate lead pipes, The Center Square, Feb. 6, 2023 at [LINK]

South Carolina

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and SC DHEC, Lead Testing in Schools and Child Care Programs [LINK]

South Dakota

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and SD DANR, Lead in Schools, accessed Feb. 7, 2023 at [LINK]

Tennessee

- “AN ACT to amend Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 49; Title 68 and Title 69, relative to water quality in schools,” Tennessee Public Chapter No. 977. Available at [LINK]

Texas

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]; and TCEQ, Voluntary Lead Testing in School and Child Care Drinking Water, at [LINK] and Program Results at [LINK]

Utah

- Utah Code Ann. § 19-4-115

- Schools and Childcare Facilities: Lead-free Learning Initiative, Utah DEQ (with links to EPA’s 3Ts for testing and sampling)

Vermont

- Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, § 1243 (see also, §§1244-48),

- Rule Governing Testing and Remediation of Lead in the Drinking Water of Schools and Child Care Facilities 12-5 Vt. Code R. § 63

Virginia

- Va. Code Ann. § 22.1-135.1

- Drinking Water Funding Program Details, VA Dept of Health accessed 1-27-23.

Washington

- The Bruce Speight Act, Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 43.70.830, [LINK]

- Schools—Lead In Drinking Water

- Dept. of Health, School Requirements for Lead in Drinking Water

- Dept. of Health, Technical Guidance for Lead in School Drinking Water

- Safe Water Sources (in Child Care) rule WAC 110-300-0235

- Dept. of Health, Testing for Lead in Drinking Water in Child Care Programs

- Dept. of Health, Fact Sheet: Directive 16-06: Lead Service Lines and Lead Components (Jan 2022)

West Virginia

- Caroline Packenham, How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water, NASBE, (Nov. 2021) at Table 1, accessed at [LINK]

Wisconsin

- Urban Milwaukee, Gov. Walker announces 35 municipalities to receive $13.8 million to remove lead service lines, June 28, 2017, at [LINK]

- “Community and utility efforts to replace lead service lines,” Environmental Defense Fund, available at [LINK]

- Wisconsin statutes 196.37 (6) est. by SB 48 (2018), at [LINK]

Wyoming

- WDE, Grant Applications for Lead Testing in Schools, accessed Feb 3, 2023 at [LINK]

Topics

Authors

John Rumpler

Clean Water Director and Senior Attorney, Environment America Research & Policy Center

John directs Environment America's efforts to protect our rivers, lakes, streams and drinking water. John’s areas of expertise include lead and other toxic threats to drinking water, factory farms and agribusiness pollution, algal blooms, fracking and the federal Clean Water Act. He previously worked as a staff attorney for Alternatives for Community & Environment and Tobacco Control Resource Center. John lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, with his family, where he enjoys cooking, running, playing tennis, chess and building sandcastles on the beach.

Matt Casale

Former Director, Environment Campaigns, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Find Out More

Good intentions, bad outcomes. Six ways impervious surfaces harm our cities and the environment

Safe for Swimming?

The Threat of “Forever Chemicals”