Climate Solutions from Day One

12 Ways Governors Can Lead on Climate Now

New governors are getting ready to take office in 20 states, from Florida to Alaska. As America’s newly elected governors prepare to take on their states’ biggest challenges, they should prioritize taking bold action on the greatest challenge of our time: climate change.

Downloads

New governors are getting ready to take office in 20 states, from Florida to Alaska. As America’s newly elected governors prepare to take on their states’ biggest challenges, they should prioritize taking bold action on the greatest challenge of our time: climate change.

Governors have extensive power to reduce carbon pollution and put their states on a path to clean energy – often with just a stroke of the pen. Over the last decade, governors have adopted sweeping emission reduction goals, accelerated the transition to clean energy, forged regional agreements to tackle climate change, and appointed leaders of state agencies empowered to implement policies to reduce pollution in buildings, at electric utilities, in transportation and throughout the economy.

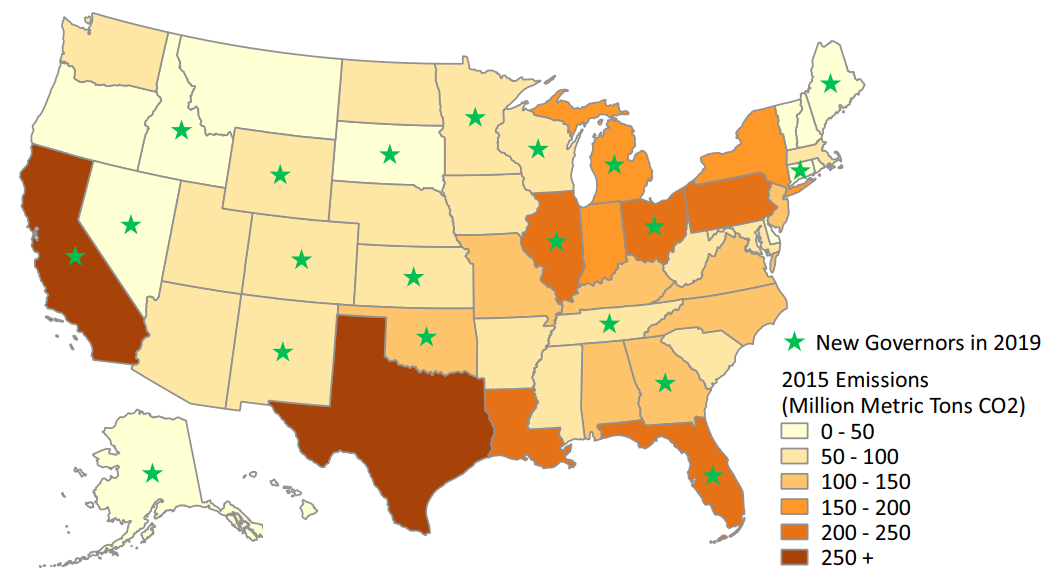

States with newly elected governors are home to 150 million people and emit 2.1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year – 45 percent of the United States total and more than any other country besides China and India.[i] The 12 actions highlighted in this report can be taken by many of America’s new governors right now – making an immediate difference in the fight against global warming.

Figure ES-1. States with New Governors for 2019 Account for 45 Percent of U.S. Climate Emissions[ii]

Governors should set ambitious goals for reducing carbon pollution and accelerate the transition to clean energy.

Action #1: Set a strong statewide emission reduction goal. An ambitious emission reduction goal can focus the efforts of state agencies and rally the public behind climate solutions. In California, Governor Jerry Brown’s 2015 order establishing a 40 percent emission reduction target led the state legislature to adopt the target by law one year later.[i]

Action #2: Set strong clean energy and energy reduction goals. Clean energy goals help focus state agencies and the public on charting a path to less energy waste and more renewable energy. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy’s offshore wind goal led to the nation’s largest offshore wind solicitation to date.

Action #3: Set goals for electric vehicles. Electric vehicle (EV) goals help states measure the progress of policies such as rebates, commercial fleet programs and expansion of EV charging infrastructure, while highlighting the need for additional policies. In Oregon, Governor Kate Brown’s executive order establishing a state EV goal also directed state agencies to begin rulemaking for an EV rebate program, and to plan and budget for the installation of EV charging infrastructure.[ii]

Action #4: Set a waste reduction goal. The process of producing and disposing of goods is responsible for 42 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. A waste reduction goal can drive states to adopt policies to increase recycling, reduce packaging, or create composting programs. In Maryland, former Governor Martin O’Malley set a goal for the state to divert 85 percent of its waste away from landfills by 2040 and achieve an 80 percent recycling rate.

Governors can ensure state governments “lead by example” by requiring state agencies to make climate-friendly purchasing decisions.

Action #5: Direct state agencies to deploy clean energy. State governments spend more than $11 billion each year on energy.[iii] Governors can direct state agencies to reduce energy use and purchase clean energy. In Massachusetts, former Governor Deval Patrick’s directive led to state operations reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 28 percent, increasing solar energy capacity nearly 400-fold, and lowering fuel oil consumption for heating by more than 19 million gallons.[iv]

Action #6: Direct state agencies to adopt and encourage electric vehicles. Governors can require state agencies to shift toward electric vehicle fleets and encourage transit agencies and education departments adopt electric buses. The nine governors who signed onto the Multi-State ZEV Task Force agreed to accelerate state agency adoption of zero-emission vehicles as one measure to help achieve a goal of 3.3 million ZEVs on the road across participating states by 2025.

Action #7: Direct state agencies to reduce waste from state operations. State governments are major consumers of disposable goods, and initiatives to reduce waste and increase recycling can make an important impact. Some best practices recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency include purchasing products in bulk, making paper documents available electronically, reusing cardboard moving boxes, reusing office furniture and supplies, and using durable dining ware. In Pennsylvania, former Governor Ed Rendell directed state government to procure Energy Star and other efficient products, and to develop conservation measures for all state-owned buildings.[v]

Governors often have the power to make policy decisions with lasting benefits for the climate.

Action #8: Set strong energy building codes. Homes, offices and other buildings account for almost 40 percent of U.S. energy use.[vi] Some governors have the authority to initiate the code amendment process and to recommend improvements in efficiency and clean energy readiness, particularly in states where building codes are amended at the state level through a regulatory rather than legislative process. In Oregon, Governor Kate Brown directed the amendment of state building codes to require, by 2025, that new homes and commercial buildings meet stringent efficiency standards and be constructed to accommodate installation of solar panels and EV charging.[vii]

Action #9: Shift transportation spending and policies to support low-carbon modes. Transportation is the nation’s leading source of global warming pollution in the U.S.[viii] Many governors are empowered through state transportation departments to allocate federal and state transportation funds. By focusing additional resources on low-emission transportation modes like walking, biking and public transit, and changing state policies that hinder those modes, governors can reduce the climate impact of transportation. In Delaware, former Governor Jack Markell directed the Delaware Department of Transportation to, whenever possible, improve infrastructure for walking or biking when building or maintaining roadway.[ix]

Action #10: Incentivize electric vehicles and adopt Cleaner Cars standards. Governors can direct state agencies to incentivize electric vehicles in a variety of ways. In some states, governors can initiate the process of adopting the cleaner vehicle standards currently in place in California and 12 other states, which set greenhouse gas standards for vehicles and increase the availability of zero-emission vehicles. In Colorado, Governor John Hickenlooper began the process of adopting cleaner vehicle standards through an executive order in 2018.[x]

Governors can limit or slow the production of climate-altering fossil fuels.

Action #11 : Limit new fossil-fuel infrastructure. Infrastructure for the production and transportation of fossil fuel – including wells, refineries, pipelines and shipping terminals – typically requires state permitting and approval. By setting high environmental standards for these facilities, or denying permission for them to operate, governors can limit the production or flow of fossil fuels through their state. In Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Wolf issued an executive order reinstating a moratorium on new leases for oil and gas development in state parks and forests.[xi]

Governors can rally neighboring states to join regional agreements to address climate change.

Action #12. Collaborate in regional climate initiatives. Electric grids, highways and pipelines cross state lines. Collaborative efforts among states can make certain types of climate action easier and create a “race to the top” dynamic that leads to more ambitious action. By entering or forming partnerships with neighboring states, governors can push forward region-wide action to reduce global warming pollution, and enlist a broad set of resources across state lines for achieving climate progress. In Virginia, former Governor Terry McAuliffe’s executive order set the state on a course to take part in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a regional power plant emissions cap-and-invest program.

In addition to these specific actions, governors can use their appointment power to name climate champions to key posts in state government.

Because each state has different laws, the actions new governors can take will vary by state. But by taking action where possible, governors have an opportunity to make a meaningful difference in the effort to protect their states and the world from the worst impacts of global warming.

[i] David Roberts, “California Gov. Jerry Brown Casually Unveils History’s Most Ambitious Climate Target,” Vox, 12 September 2018, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20181031003038/https://www.vox.com/energy-and….

[ii] Oregon Office of the Governor, Executive Order 17-21: Accelerating Zero Emission Vehicle Adoption in Oregon to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Address Climate Change, 6 November 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181113215148/https://www.oregon.gov/gov/Do….

[iii] American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, State Government Lead by Example, archived on 14 November 2018 at https://web.archive.org/web/20181114165617/http://aceee.org/sector/state….

[iv] Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, Leading by Example Progress: Overview, archived on 27 November 2018 at http://web.archive.org/web/20181127142005/https://www.mass.gov/info-deta… more details available at Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, Measuring Progress on Executive Order 484, October 2014, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20180912085518/https://www.mass.gov/files/doc….

[v] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Governor’s Office, Executive Order 2004-12: Energy Management and Conservation in Commonwealth Facilities, 15 December 2004, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20161231221156/http://www.oa.pa.gov/Policies/….

[vi] U.S. Energy Information Administration, How Much Energy Is Consumed in U.S. Residential and Commercial Buildings?, 3 May 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181113215538/https://www.eia.gov/tools/faq….

[vii] Oregon Office of the Governor, Executive Order 17-20: Accelerating Efficiency in Oregon’s Built Environment to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Address Climate Change, 6 November 2017, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20180309093031/http://www.oregon.gov/gov/Docu….

[viii] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, archived on 13 November 2018 at http://web.archive.org/web/20181113121125/https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissio….

[ix] Delaware Governor’s Office, Executive Order Number Six – Creating a Complete Streets Policy, 24 April 2009, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20180706202052/https://governor.delaware.gov/….

[x] Colorado Office of the Governor, Executive Order B 2018 006: Maintaining Progress on Clean Vehicles, 18 June 2018, archived at https://archive.org/wayback/available?url=https://www.colorado.gov/gover….

[xi] Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Gov. Corbett Issues Executive Order Protecting State Forests, Parks from Gas Leasing That Involves Surface Disturbance, 28 May 2014, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20170926022538/http://www.apps.dcnr.state.pa…..

[i] U.S. Energy Information Administration, Energy-Related Carbon Dioxide Emissions by State, 2000-2015, January 2019, available at https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/state/analysis/; U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics, accessed at https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/data/browser/ on 30 November 2018.

[ii] Ibid.

Topics

Find Out More

Carbon dioxide removal: The right thing at the wrong time?

Fact file: Computing is using more energy than ever.