Pennsylvania’s Pristine Waterways and Microplastics

A Survey of Exceptional Value, High Quality, and Class A Trout Rivers and Streams

Executive Summary

Plastic is everywhere and in everything. It’s used as packaging, it’s in food service products, and it’s in clothing. All told, Americans generate over 35 million tons of plastic waste every year, but less than 6% is recycled. In fact, the U.S. throws out enough plastic every 16 hours to fill the Dallas Cowboys stadium, and that amount is increasing annually.

Often when talking about plastic pollution, the images that come to mind are sea turtles and birds ensnared in bags or straws, massive trash gyres in the Pacific Ocean, or whales washed ashore with hundreds of pounds of plastic waste in their stomachs. So it may not be surprising that 60% of all seabird species have ingested plastic, with that number expected to rise to 99% by the year 2050. Studies have also estimated that by 2050 there will be more plastic in our oceans than fish.

Plastic pollution is also a pressing issue right here in Pennsylvania. For example, in a single year, the Philadelphia Water Department removes 44 tons of trash from a 32 mile stretch of the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, 56% of which is plastic waste. In Pennsylvania, plastic is the most common form of visible litter. In fact, the Department of Transportation spends over $13 million every year cleaning up just roadside litter. The problem is so widespread that nine of the largest cities in Pennsylvania spend over $68.5 million every year on litter and illegal dumping, with $46.7 million of that going toward litter abatement.

But litter alone doesn’t capture the full scope of plastic pollution. Research suggests that we could be not counting 99% of the plastic that makes its way into the environment. That’s because plastic doesn’t degrade in the environment like an apple or a piece of paper, instead it breaks into smaller and smaller pieces of plastic called microplastics. Microplastic is plastic less than 5mm in length, or smaller than a grain of rice. They’ve now been found in the deepest depths of the ocean and on the highest mountains in the world.

A growing area of concern regarding our plastic waste is the environmental and public health threat posed by these microplastics. They are severe suffocation and starvation hazards to wildlife and have been found in our air, food, and bodies. Microplastics also attract pollutants that may already exist in the environment at trace levels, accumulating toxins like DDT & PCBs and delivering them to the wildlife that eat them, often bioaccumulating through the food chain. And the evidence is mounting that humans not only ingest microplastics, but that those plastics remain in the body and cause harm. It’s estimated that on average, humans ingest 5 grams of plastic every week, roughly equivalent to the weight of a credit card or single-use plastic bag. Microplastic has been found in human blood and even the lungs of living patients. And although not too much is known about the full scope of health effects of microplastics in humans, plastic, and the chemicals it contains, can cause endocrine disruption, hormonal effects, and reproductive disorders.

And microplastics don’t arrive in the environment from just one source. Plastic littered on roads, in streams, or in the ocean can release tons of microplastics, but plastic waste disposed of in landfills can also release microplastics into the environment through wind, rain, and landfill leachate. The burning of plastic or other waste can also create airborne microplastic particles. Microbeads from cosmetic and personal care products can enter the environment at their manufacture or through sinks and drains. Nurdles, the raw plastic feedstock that are used to make new plastic items, are lost by the millions every year. Synthetic materials in car tires release microplastics onto roads that are swept into stormwater infrastructure.

Clothing and other textiles are also a major source of microplastics. Fibers are one of the most commonly found types of microplastic and they’re sourced from synthetic and hybrid materials like fleece. Normal wear and tear will release microplastics into the air, and cleaning these textiles in a washing machine releases millions of microfibers into wastewater infrastructure that treatment plants are unable to fully filter out.

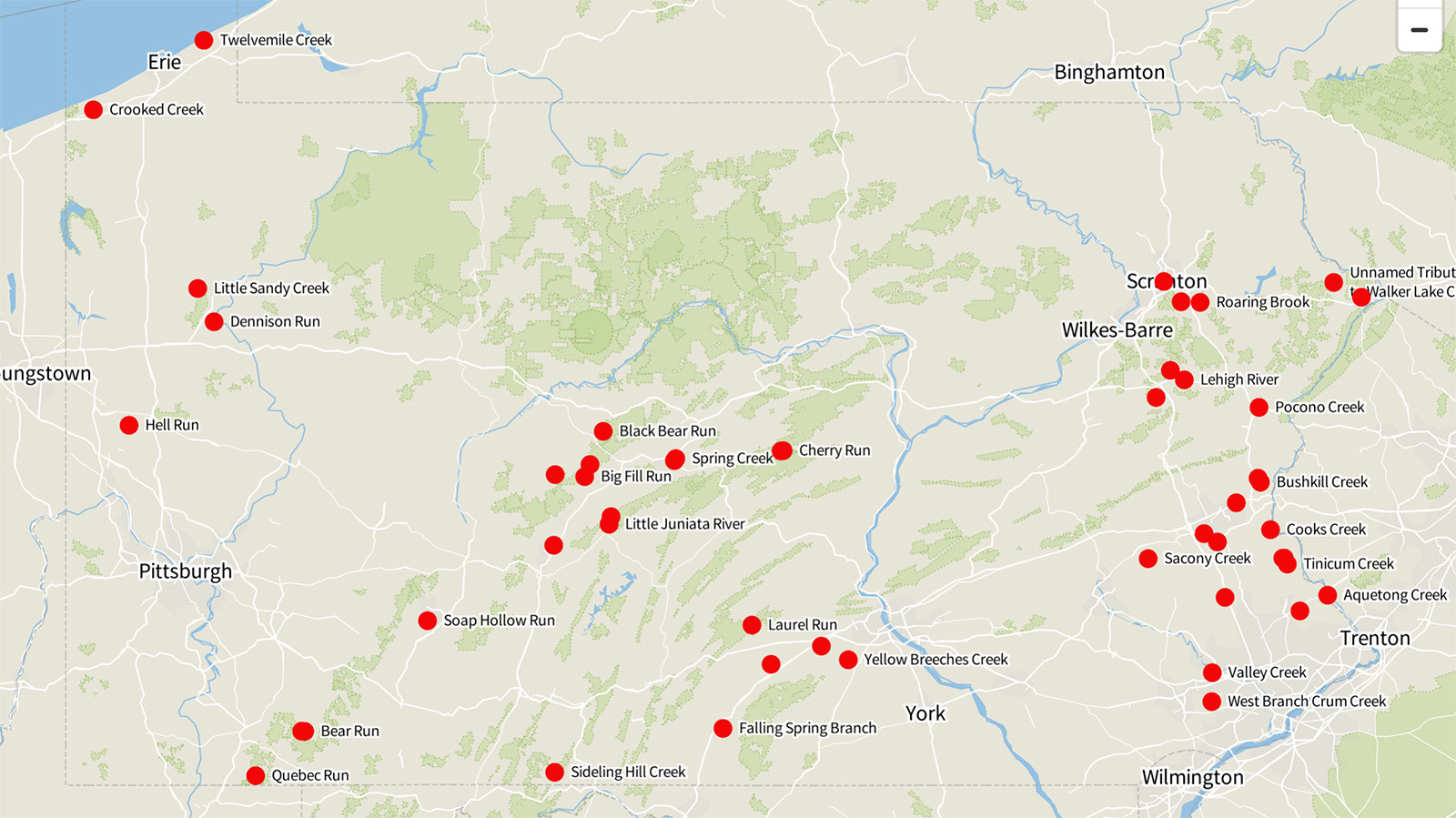

To better understand the scope of the microplastic problem in Pennsylvania, the PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center sampled 50 of Pennsylvania’s Exceptional Value (EV), High Quality (HQ), and Class A Cold Water Trout Fishing (Class A) streams. We found microplastics in 100% of our samples. Unfortunately, these samples come from waterways that are considered among the cleanest and of the highest ecological value in the Commonwealth.

Our project took samples from the identified waterways from winter 2021 through spring 2022 and tested them for four types of microplastic pollution:

- Fibers: primarily from clothing and textiles;

- Fragments: primarily from harder plastics or plastic feedstock;

- Film: primarily from bags and flexible plastic packaging;

- Beads: primarily from facial scrubs and other cosmetic products.

The results found were troubling:

- 100% of EV, HQ, and Class A Trout streams sampled had microfibers;

- 84% of sites sampled had microfragments;

- 84% of sites sampled had microfilm;

- Only 2% of sites had microbeads.

It’s clear that the scope of plastic pollution in Pennsylvania extends far beyond what was previously thought. These are the cleanest and best protected waterways in the Commonwealth. And while many of the waterways sampled had little to no visual litter at the point of access, our samples found that Pennsylvania’s most pristine waterways continue to be contaminated with plastic pollution.

In order to address the environmental crisis being caused by our overreliance on plastics, our leaders at the federal, state, and local levels should immediately implement the following policies:

- Municipalities should pass local bans and other restrictions on hard to recycle single use plastics, such as bags, polystyrene, bottles, straws, and utensils.

- Cities should develop green infrastructure and stormwater programs to help stem the tide of plastics and microplastics being washed into our waterways and surrounding environment.

- State legislators should defend against any proposals meant to preempt or restrict the ability of the Commonwealth’s municipalities from implementing local plastic ordinances.

- The Pennsylvania General Assembly and United States Congress should pass bottle deposit requirements and producer responsibility laws to shift the burden of waste onto those who create the pollution in the first place.

- The General Assembly should modernize Pennsylvania’s cornerstone recycling law, Act 101, in order to bring the Commonwealth’s waste management into the 21st century.

- State and local legislators should oppose any proposed subsidies or other incentives that will continue to promote society’s reliance on single-use plastics and double down on the fossil fuel-to-plastics pipeline.

- State and federal officials should pass policies that prevent overstock clothing from being sent to landfills so that clothing manufacturers and retailers stop producing more clothing than we could ever need.

Microplastics found in Pennsylvania’s cleanest streams

Pennsylvania’s Pristine Waterways and Microplastics Appendix

Microplastics in Pennsylvania

Authors

Faran Savitz

Zero Waste Advocate, PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center

Faran works on PennEnvironment’s Zero Waste program, working to reduce plastic waste in Pennsylvania and to protect our parks and open spaces. Faran’s work has included helping to write and pass bans on single-use plastic across Pennsylvania, including in Philadelphia, promoting the Zero Waste PA package of legislation, protecting major conservation laws like the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and publishing the report “Microplastics in Pennsylvania,” which was the result of a project testing more than 50 Pennsylvania waterways for microplastic pollution.