Testimony on water & wastewater in fracking

I want to talk about the environmental risks posed by oil and gas wastewater, the opportunity to recycle the wastewater for reuse in the oilfields, and the danger of reusing it for other purposes such as agriculture or discharge into our waterways.

My testimony today before a joint hearing of the House Natural Resources and Energy Resources committees.

Good afternoon Chairmen and members,

My name is Luke Metzger and I am Executive Director of Environment Texas, a non-profit advocate for clean air, clean water and open spaces.

I want to talk about the environmental risks posed by oil and gas wastewater, the opportunity to recycle the wastewater for reuse in the oilfields, and the danger of reusing it for other purposes such as agriculture or discharge into our waterways.

First, we know oil and gas production uses a lot of water in Texas. According to a Duke University study, water use per well in the Permian Basin increased 767% between 2011 and 2016. In total, the San Antonio Express News review of Fracfocus data, the oil and gas industry used 39.7 billion gallons of water to drill wells in Texas in 2016 and that number is expected to grow to almost 100 billion gallons by next year. That’s more than twice than what Austin uses in a year.

While that might work out to a low statewide percentage, in some rural counties it can account for 90% of total water use.

Most of this water use occurs in some of the most drought prone parts of our state. This can leave local residents without water, like in 2013, when the west Texas town of Barnhart ran out of water due the drought and demand for water to frack wells. The town had to truck in bottled water for residents while a backup well was drilled.

This water use also raises concerns about depleting aquifers and springs and harming wildlife which depend on those waters. For example, the Comanche Springs Pupfish is endangered because more water is being pumped from the ground than is being replaced by rainfall.

And climate change will strain water resources even further.

In addition to using a lot of water, drilling generates an enormous amount of wastewater: an estimated 300 billion gallons every year in Texas. That’s enough to fill 4 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

This wastewater is subject to spills, due to pipes breaking, well blow outs, wastewater pits overflowing due to flooding, or even deliberate dumping. There were at least 1200 spills of wastewater reported to Railroad Commission (RRC) district offices in 2015. Unfortunately, due to unclear and lax reporting requirements, that figure is likely conservative and it was difficult to obtain. The RRC should strengthen reporting requirements so we can more accurately and easily measure the total volume of produced water and spills.

While the name “saltwater” sounds innocuous, it can in fact cause severe environmental damage when spilled. The wastewater is many times saltier than seawater and can contaminate groundwater and ruin soil for generations.

In 2011, according to the Upper Trinity Groundwater Conservation District in North Texas, open pits of drilling mud waste contaminated four family water wells in Montague County. In 2015, the RRC found that an oil company illegally dumped 3 million gallons of wastewater in pastures out by Fort Stockton. The groundwater conservation district there is worried the groundwater may have been contaminated.

Perhaps the most famous case started in the 1920s, when oil was struck at the Santa Rita No 1 well on land owned by UT. Wastewater then was managed by releasing it directly onto West Texas soil, before the industry and regulators fully realized the negative consequences of this practice. About one billion barrels of wastewater were spread across 2000 acres, creating the Texon Scar, a patch of dead earth so large it can be seen from space. That land is still being clean up today, almost 100 years later.

This experience should serve as a cautionary tale as you consider new ways to dispose of or use wastewater. We should not leap before we look very, very closely.

In addition to high salinity, fracking wastewater contains highly toxic substances that can persist in the environment for many years. It can potentially contain any combination of over 1600 different chemicals. In one analysis of fracking fluid chemicals, 157 were found to be linked to reproductive or developmental health problems, and toxicity information was lacking for hundreds of others. Naturally occurring underground chemicals include oil byproducts, which can cause kidney and liver damage and reproductive problems, and radioactive materials, which can cause lung and bone cancer, lymphoma and leukemia.

Most wastewater is injected underground in to deep disposal wells, but these wells can also fail over time, allowing the wastewater and its pollutants to mix with groundwater or surface water. For example, a disposal well contaminated an aquifer near Midland back in 2005. More recently, we’ve learned that waste injection can cause earthquakes. I understand the RRC staff have been thinking about updating their UIC disposal well rules. We encourage them to do that.

To reduce harm to the environment and public health and safety, we also need to reduce the amount of potable water used in drilling.

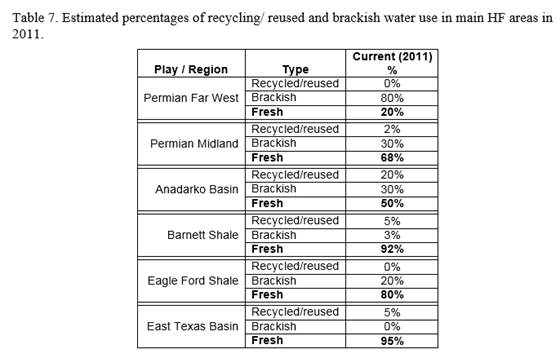

Brackish water is increasingly being used in parts of the Permian, which is good news. And though several drilling companies have invested in water recycling infrastructure and other businesses focused solely on water recycling technology have sprung up, only a fraction of the flowback water from fracking that could be recycled is actually recycled. A 2011 UT study calculated that only about 2 percent of flowback in the Permian Basin is recycled and reused. That amount has likely increased since then, but we don’t have the data and it probably is still no higher than 10%. The low rate is due to the cost of recycling and contracts that obligate drillers to buy water from the landowner.

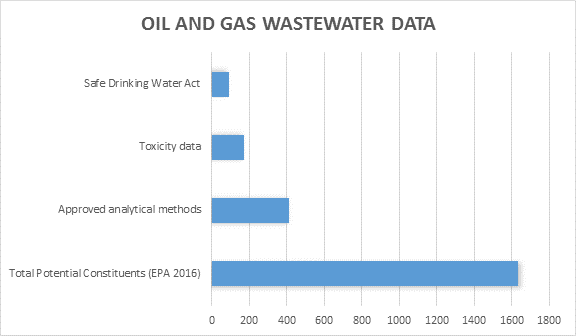

We are very concerned though about talk of reusing wastewater outside of the oilfield, in agriculture or discharging to waterways. I’ve passed out a chart which explains some of our concerns.

As I mentioned, we’re talking about as many as 1600 different chemicals in produced water. EPA has approved methods for detecting only about 400 of those chemicals. Next, we only have data on the toxicity for less than 200. And finally, the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates for just 89 of those.

So don’t buy the claims that treated wastewater is fresh and safe. For example, look at ethylene glycol, the main ingredient in antifreeze and a toxin to humans and animals. It’s one of the top 10 most used chemicals in hydraulic fracturing – repeatedly showing up in produced water, yet, it is not one of the chemicals regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act. That means treated produced water could meet drinking water standards even where ethylene glycol is present.

In conclusion, we urge you to prohibit the use of oil and gas wastewater for agriculture, drinking water or discharge to waterways unless and until independent research proves it safe.

Authors

Luke Metzger

Executive Director, Environment Texas

As the executive director of Environment Texas, Luke is a leading voice in the state for clean air and water, parks and wildlife, and a livable climate. Luke recently led the successful campaign to get the Texas Legislature and voters to invest $1 billion to buy land for new state parks. He also helped win permanent protection for the Christmas Mountains of Big Bend; helped compel Exxon, Shell and Chevron Phillips to cut air pollution at four Texas refineries and chemical plants; and got the Austin and Houston school districts to install filters on water fountains to protect children from lead in drinking water. The San Antonio Current has called Luke "long one of the most energetic and dedicated defenders of environmental issues in the state." He has been named one of the "Top Lobbyists for Causes" by Capitol Inside, received the President's Award from the Texas Recreation and Parks Society for his work to protect Texas parks. He is a board member of the Clean Air Force of Central Texas and an advisory board member of the Texas Tech University Masters of Public Administration program. Luke, his wife, son and daughters are working to visit every state park in Texas.