Donate Today

Why you should install solar panels and batteries, how well does solar work in Alaska, how to pay for your solar panels and batteries, and how to get started adding solar panels to your roof.

Donate

The short answer to this question is that Alaska gets enough sun for solar to be a good choice in many places in the state, although there will be significant seasonal variability. Irradiance is the measure of light energy from the sun hitting the earth, and while Alaska has lower irradiance than many places, it is similar to Germany’s, which is one of the solar leaders of the world.

There is a longer answer as well.

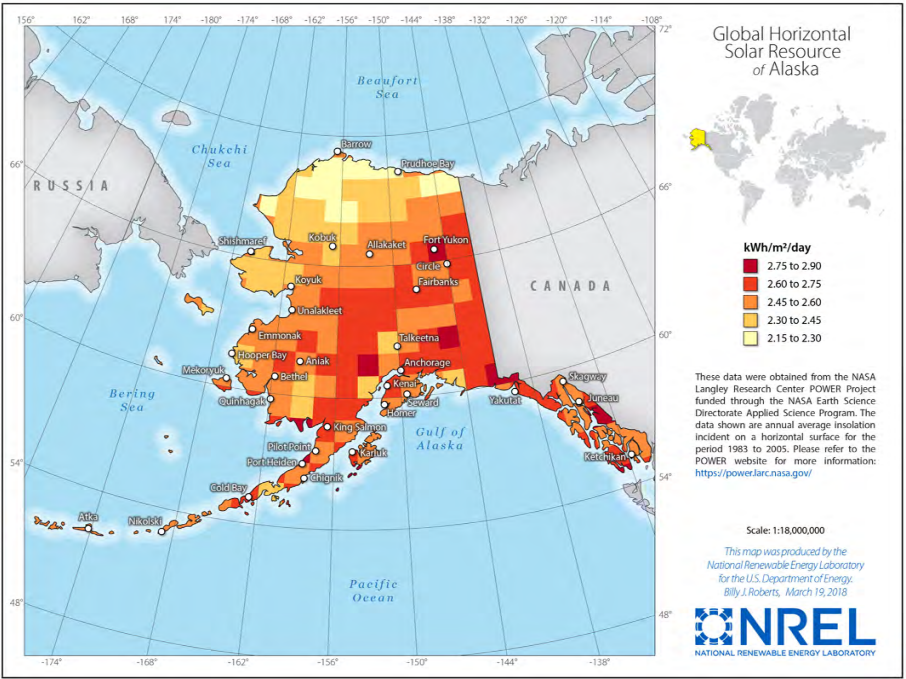

Global radiation measured on a horizontal plane (as if panels were on a flat roof) is used to create this insolation map of Alaska which shows the average daily solar energy received throughout AlaskaPhoto by Billy J. Roberts, National Renewable Energy Laboratory for DOE | Public Domain

As seen in the above image, there are many places in Alaska that get quite a bit of sun or irradiance. Obviously, the range that makes up those annual averages are quite large. Anchorage maxes out at 280 W/m² and Fairbanks maxes out at 100W/m² on the winter solstice, but by the spring equinox Anchorage maxes out at 841 W/m² and Fairbanks at 790 W/m², and then by the summer solstice Anchorage maxes out at 980 W/m² and Fairbanks at 970 W/m². These maximums do not take into account temperature, humidity, albedo (reflected light, off of snow for instance), weather or other climatic factors. Some of these unaccounted for factors, like cloudiness, can decrease the irradiance while others, like albedo, can increase the irradiance.

All that to say, arrays will produce very little to no electricity from around the middle of November until the end of January, but in the spring and summer, arrays can harness a lot of potential energy, and the fall falls in the middle. This tool from NREL will allow you to enter your address and get a good idea of how an array would perform throughout the year for your home.

There is a wide range with costs generally falling between $10,000 and $30,000. In 2019, urban Alaskans were paying $1.25- $3.50/watt and remote Alaskans were paying $2.20-$4.60/watt.

Yes. There is some variance throughout the state, but due to high energy costs in Alaska, folks will generally end up saving money by installing solar on their roof.

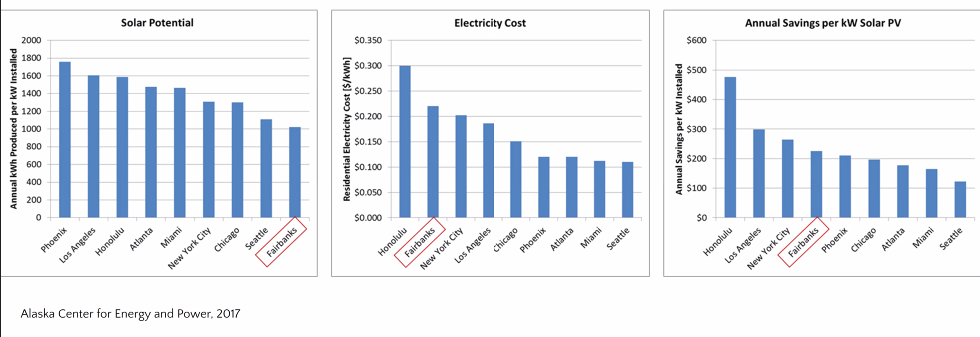

Despite lower solar potential than many other major cities in the U.S, Fairbank’s high energy costs put the potential savings from solar fairly high in the rankings.Photo by Alaska Center for Energy and Power, 2017 | CC-BY-SA-4.0

The ITC has been restored to the full 30% deduction off federal income tax, and that credit will last through 2032. The credit will begin reducing to 0% by 2035. Even if your tax liability isn’t that high, the tax credit can help you because unused credit can be carried to the following year for deduction (so if you pay $15,000 for an array, and only owe $3000 in federal income tax, you will get credited $3000 in year one and $1,500 in year two).

Tax exempt entities like houses of worship and non-profits can qualify for direct pay options, so they too can take advantage of the tax credit. Commercial operations are also eligible for a 30% tax credit.

The Alaska Center coordinates the Solarize program which helps communities buy solar panels as a group, which can allow for discounts that range from 10-17% before the federal tax credit.

Alaska’s net metering rule applies to systems 25kW or smaller and only for large utilities. Customers are paid the amount the utility avoids spending on fuel and operations for the electricity they send back into the grid. That cost is generally less than the retail cost of the electricity. There is a cap on the total energy the utility will buy from customers, and that cap varies by utility, but is never less than 1.5% of the total energy use in the utility. Net usage is calculated monthly.

There is no net metering for residents in rural Alaska, and costs for labor and transportation of materials is significant. Often the better way for rural communities to invest in solar is in a coordinated effort with the community and local utility. For communities who largely rely on diesel, adding solar can significantly reduce energy costs.

You can review a full list of incentives available to folks in Alaska here.

Alaska hasn’t passed a community solar bill as of 2023, but SB 152 was introduced during the Spring session. Community solar allows renters, folks with shady roofs, or people who don’t quite have the resources to invest in a full array for their own roof to buy into a community solar project. If the community solar bill passes, developers will be able to take advantage of some great credits:

Battery banks can range from $5000-$20000 depending on type and number.

Panels, batteries, labor, permitting, and equipment are all included.

When deciding on whether it financially makes sense to add solar panels, you’ll consider how long it will take for you to start saving more money than the installation cost. Moving obviously changes that calculation. However, Zillow did a study in 2019 and found that homes with solar panels sell for an average of 4.1% more than comparable homes without arrays, so moving shouldn’t compromise your investment.

There are a lot of solar panels on the market, and it can be tough to figure out which ones make the most sense for your home. EnergySage has a great comparison tool to review as well as a list of their top choices. Your contractor may have a specific panel or panels that they install, so you’ll want to take that into consideration as well. Outside of that, there are a few different specifications you’ll want to consider:

Mono or Poly?

There are two primary types of solar panels. Monocrystalline have cells with a single silicon crystal. These panels are generally black, and they’re more efficient. Polycrystalline solar panels have cells with several silicon crystals melted together. These panels are typically blue and cost less.

Efficiency

Efficiency compares the energy your panel generates to the sunlight hitting it. Higher efficiency means more electricity. Most panels have a 15-20% efficiency, but there are some popular brands exceeding 21%. High efficiency is a key consideration for most folks in Alaska because it will help maximize your energy generation in low-light conditions, which are common in many places in Alaska. Generally, it’s recommended that Alaska households aim for 20%+.

Capacity

The wattage, capacity, or solar output is the amount of direct current (DC) electricity the panel produces under standard conditions. Higher wattage panels generate more electricity. Most recommended panels generate between 350 Watts to 450 Watts.

Temperature coefficient

Solar panels have reduced performance in hot weather (starting at about 77 degrees F), and the temperature coefficient measures how much the capacity will decrease as the temperature increases. A lower temperature coefficient means a panel will lose less of its capacity on hot days. In places like Anchorage, this probably is not a key concern because there aren’t that many days where the temperature exceeds 77 degrees. (However, climate change puts an asterisk on that assumption). In Fairbanks, where summer days can get very hot, this is a more important consideration.

Lifespan and warranty

The assumed average lifespan of a solar panel is somewhere between 25 and 30 years. A good warranty can help ensure your investment pans out. Solar panels generally have two components to their warranties: a product warranty that covers replacement if a product defect causes a panel to stop working and a power or performance warranty that will cover replacement if your panel reduces output by a certain percentage by the specified warranty term. When considering a warranty, you should also see whether labor and shipping are included and consider whether the brand is likely to be around to follow through on a warranty (ie, there is safety in an established company).

What about shingles?

If you’ve got an aesthetic that panels don’t quite fit, there are also building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) solar shingles and solar tiles. However, shingles cost more, are less efficient, and produce less power. If you need to replace your roof anyway and have an aesthetic in mind, solar shingles might be the right fit.

Number of panels=system size/production ratio/panel power output

Ultimately, this depends on the capacity of your panels, how much energy you consume, and where you live. The average number of panels is somewhere between 17 and 21. If you run a really efficient home, this number will go down. If you have transitioned your heat, car, and cooking to electric, you might be on the higher end of this range. The average system in Alaska is around 5kW.

Solar panels produce direct current (DC) power, but most of your home and appliances run on AC (alternating current), so you’ll need an inverter to convert your electricity into a form your house will run on. There are three main types of inverters– string, micro, and optimized string. String converters are relatively inexpensive, durable, and easy to maintain, however if one panel has reduced performance due to shading, the output of all panels on that string will be reduced as well. Microinverters cost a little more and are on your roof which makes maintenance tougher, but are unique to each panel, so the performance of one panel won’t impact another and can give you panel level analysis of your system. Optimized string inverters are the mix because they allow for each panel to output its max regardless of the other panels, but don’t offer individual panel level analysis. EnergySage has a nice comparison guide for inverters as well.

Generally, the rule of thumb is to redo your roof before adding solar if it has less than five years less. The big thing to consider is that when you replace your roof, you’ll have to also pay to uninstall and reinstall the panels, so you’ll want to factor that cost in- generally around $3000.

There are a few different types of batteries, and each has pros and cons.

Chemistry Types

Lithium ion batteries: These are one of the most common choices of batteries. Lithium compounds act as the electrode in all of these, but there are a few different chemistries available. One common type is lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC), which are power dense meaning they don’t take up much space in comparison to their storage potential and another is lithium iron phosphate (LFP) which are less power dense but tend to function well for longer. Lithium ion batteries generally last between 10 and 15 years.

Lead acid batteries: These batteries have different lead compounds acting as two electrodes, a positive and a negative, and an acidic electrolyte. Lead acid batteries take up a lot of space and can’t discharge fully- they need to maintain at least 50%. These often have a shorter life span, sometimes only 5 years, but personal experience indicates these can last 15 with good care.

Flow batteries: These batteries pass ions back and forth between two tanks of liquid. They all can take up a lot of space, but can store a lot of energy and may be able to last up to 30 years. These are somewhat rare now, but have potential to become very popular.

Current Type

Batteries store direct current (DC) electricity, just like solar panels generate. However, most homes and appliances run on alternating current (AC), so you need an inverter to convert the electricity into a usable form. Every time you convert electricity, you lose a little. AC coupled batteries will convert the electricity that comes from the panels to AC and then back to DC for storage and then back to AC for use, that adds up. A DC coupled battery will take the power directly from the panels in DC, and then the inverter will convert it to AC when you use it, which is more efficient. However, you’ll need a hybrid inverter for this that can convert from both solar and storage, and they’re sometimes not quite as proficient. There is a trade off. Generally adding storage later will be AC coupled, while if you do everything at once, you might choose DC coupled.

What happens in the winter?

Solar panels won’t generate electricity when it’s dark or when they’re covered in snow, so generation decreases significantly in the winter as discussed above. Up until mid-November and after February, panels can generate electricity. Light dustings of snow will melt quickly, but you may want to remove heavier spring snow to maximize performance. You should confirm with your provider that none of your actions will void your warranty, but some people will use a soft snow brush. Panels will be safe under a similar load of snow as your roof.

You should also talk to your provider about the angle of your panels throughout the year, and whether it’s adjustable. Sometimes there is an option to increase the angle to help capture more light when the sun is far down in the southern sky. Otherwise, it makes more sense to angle your panels to maximize Spring and Summer production.

What winter care will my batteries need?

Just like smartphones, solar batteries can perform more poorly in the extreme cold (or extreme heat). You’ll need to ensure that your batteries stay at an appropriate temperature during the winter. If they’re in a crawlspace, garage, or other location, you’ll want to ensure that some heat reaches them, and that they are well insulated. Outdoor locations are probably not a smart choice in Alaska.

You’ll also want to make sure that your batteries stay somewhat charged in the winter. They will last longest if they stay above a 40-50% charge depending on battery type.

In some parts of Alaska, you might only have one option for an installer, or you might even need to have someone come into your community from somewhere else. If this is you, coordinating with your neighbors to do some joint installations can reduce overall costs.

Some installers prefer to have a signed contract before an engineer checks your roof and electrical panel (sometimes these will need to be updated before you add your array). That’s okay as long as your contract has an out if your home isn’t suitable yet. Many of these visits are done in person, but sometimes they are done virtually, and if you live in a community off the road system without a local solar installer, a virtual site visit might be the best fit.

Once you’ve reviewed bids and chosen an installer, you’ll sign a contract. Make sure to read it carefully paying particular attention to details on cost, equipment, cancellation terms, and clauses.

The two most common ways to pay for a system is upfront with cash or using a solar loan either from a bank or through your solar company. Some folks will opt for a solar lease. There are pros and cons to each of these options, and you’ll have to decide based on your financial situation and savings goals.

Before your solar company installs your system, they will most often take care of a set of paperwork that covers permits and interconnection to the grid. There are some labor shortages in Alaska right now in the solar industry, so you should talk to your contractor about what you can expect as a timeline. The team will include an electrician in addition to folks who will put the panels on your roof. After your system is installed, your utility will need to give you permission to operate (PTO) before your system is turned on. Most of the time, someone from your utility cooperative will come take a look at your system and install or update a meter to track the energy you send back into the grid. After you have your PTO, you can turn your system on and start generating electricity.

Maybe. Installing solar panels requires some electrical work skills, so it’s important to be cautious and not exceed your abilities. That said, do it yourself installation is more common in rural areas, especially when panels won’t be hooked up to a grid. Not all utilities will integrate a system set up by a non-certified individual, so if you choose this route, you should confirm with your utility before starting that they will give you permission to operate.

I get this all the time, does solar work in Alaska, really? And, yeah, it works great. It makes people money and gives them power.Ben May

Owner of Alaska Solar

Dyani runs campaigns to promote clean air, clean water, and open spaces in Alaska. She lives in Anchorage and loves to hike, ski and cook yummy food.