Southcentral Alaska’s Water and Microplastics

A Survey of Water Bodies in Southcentral Alaska

100% of tested Southcentral Alaska water bodies contain microplastics.

Downloads

Executive Summary

Plastic is ubiquitous– packaging, clothing, electronics, take out containers, and toys are just a few examples of items commonly made with plastic. Leo Baekeland patented the first fully synthetic plastic a little over a century ago and since then, humans have generated over 7 billion metric tonnes of plastic waste, and recycled less than 10% of it. Instead of moderating our plastic use, we’re actually increasing it. Globally, we produced 390.7 million metric tons of plastic in 2021, which is 40% more than was produced in 2011.

Marine debris (much of it plastic) coats many of Alaska’s shores, and experts predict it will cost over $100 million to clean the pollution up, and more continues to wash up from the massive trash gyres in the Pacific. Marine entanglement from trash and fishing gear is common enough in Alaska that multiple stranding hotlines are set up. On land, the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce coordinates an annual city clean up in May, and Anchorage Waterways Council hosts a simultaneous creek cleanup. Similar programs are set up in many other communities across the state, but litter is still a common sight.

Steller sea lion with plastic packing band cutting into neck in Kenai Fjords National Park.Photo by ADF&G NOAA Fisheries | Public Domain

Litter and plastic debris are only a portion of the plastic waste in the environment. A recent study in the Atlantic Ocean found that only 1% of the plastic was big enough to be clearly visible with the naked eye and floating near the surface. A large share was micro or nano- pieces smaller than 5mm. When animal and plant based litter enters the environment, microbes including bacteria and fungi will break it down into basic chemical elements like carbon, potassium, nitrogen and other key minerals that in turn feed new life. However, plastic litter is composed of artificial chains of molecules in repeating patterns called polymers, and neither bacteria nor fungi have much success breaking them down into their basic components. Over time, friction and heat will break the plastic into smaller and smaller pieces, but they’ll still be plastic and unable to nourish new life for a very long time.

Plastic doesn’t just persist in the environment, it threatens wildlife and public health. Larger pieces of plastic are laceration and starvation hazards. The smaller pieces have been found in our rain, air, and human bodies. Plastic additives include endocrine disrupting chemicals and attract toxins like DDT, PCBs, and heavy metals. Those toxic chemicals can bioaccumulate through the food chain, causing problems for animals and humans alike.

As previously mentioned, microplastics enter our environment through a myriad of pathways and move through ocean and atmospheric currents, precipitation, and wind. Litter, illegal dumping, and landfill leakage are all obvious culprits. Microfibers are a prevalent type of microplastic and are introduced to the environment when we wash synthetic clothing. Wastewater treatment plants don’t fully filter these fibers out and approximately 40% end up in our waterways, oceans, and drinking water. The production of new plastic products uses pellets which are often lost and end up in waterways. Packaging and the process of creating products like bottled water can also cause microplastic contamination.

Our waterways are a prime location to test for microplastics. Alaska’s watersheds are largely geographically isolated, with the exception of parts of Southeast which are downstream of Canada. They provide drinking water for residents, habitat for fish and other aquatic life, and are both economically and culturally vital to the state. Southcentral Alaska is home to less than half a million people (the majority of the state’s population) and hosts a little under two million visitors annually. Microplastic testing in Southcentral Alaska provides additional insight into atmospheric redistribution of microplastics, key fishery exposure, and local information about drinking water.

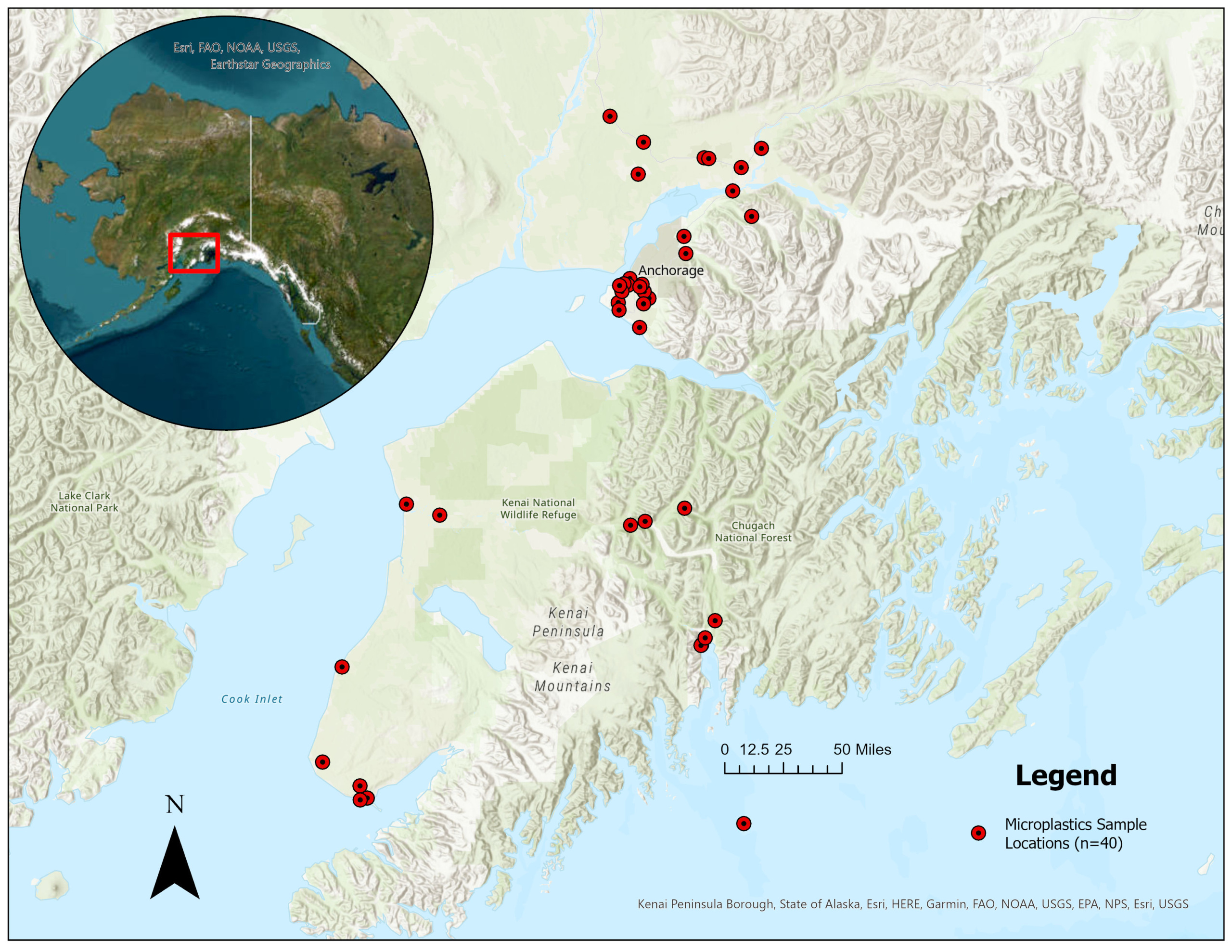

To better understand the scope of the microplastic problem in Alaska, Alaska Environment Research and Policy Center staff and volunteers sampled 39 water bodies in Southcentral Alaska. We found microplastics in 100% of our samples.

Red dots indicate where samples were taken.Photo by Sean Kelly | Used by permission

Our project took samples from waterways between June and September 0f 2023 and tested them for four types of microplastic pollution:

- Fibers: primarily from clothing, textiles, and fishing line;

- Film: primarily from bags and flexible plastic packaging;

- Fragments: primarily from harder plastics or plastic feedstock;

- Beads: primarily from facial scrubs and other cosmetic products.

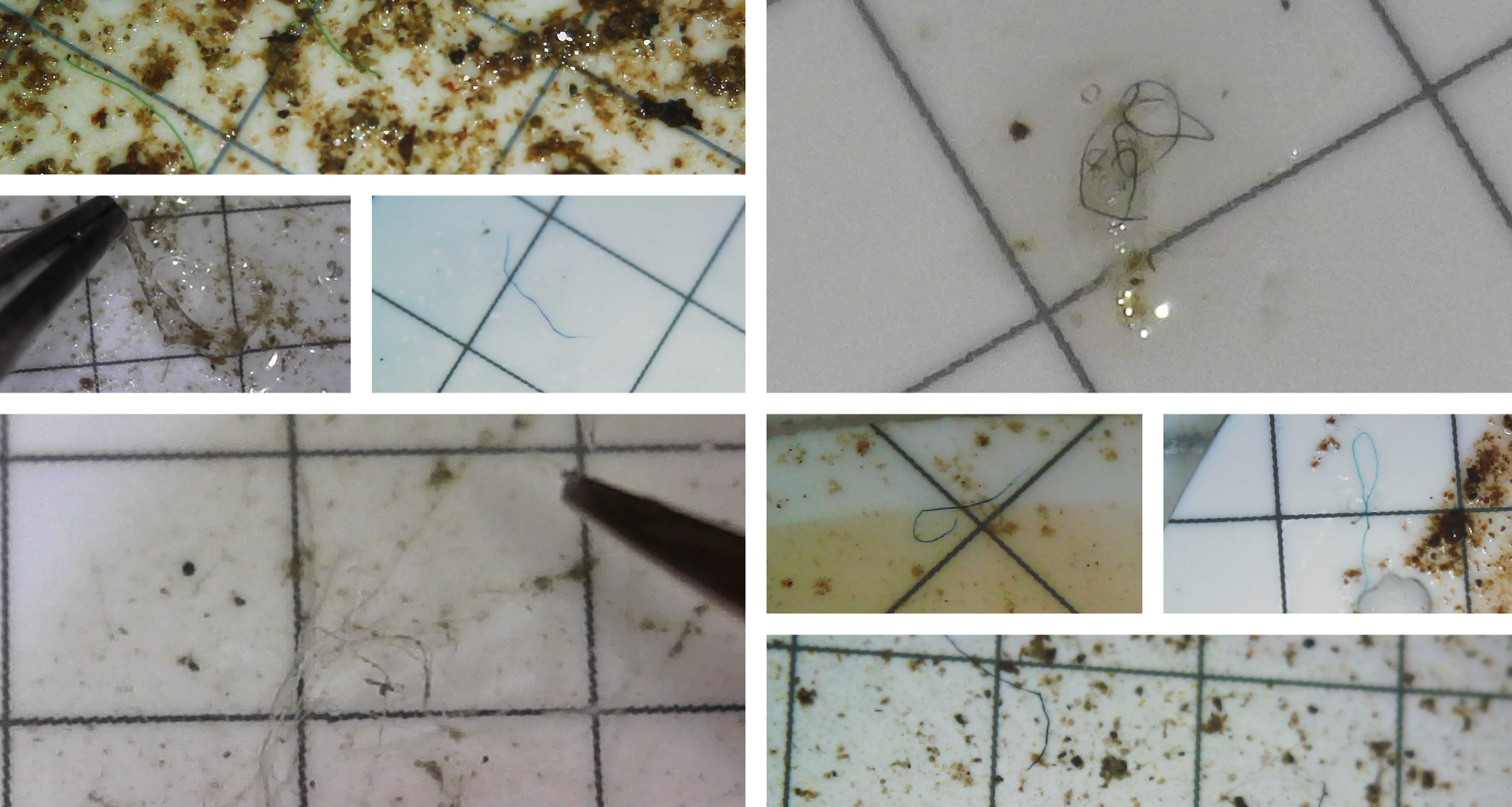

Microfibers were by far the most prevalent microplastic found in samples, and were found in 100% of samples. Micro fragments and films showed up in fewer locations, but were present in 20.5% and 33.3% respectively. Alaskans and tourists are almost certainly responsible for some of the microplastic pollution, but distribution patterns indicate some of the microplastic pollution is being swept in from other places as well.

Moving left to right, top to bottom: fibers from Lake Wasilla, fiber wrapped around a film from Sand Lake, film from Tern Lake, fiber from tap water in the U-Med neighborhood of Anchorage, fibers (likely fishing line fragments) from Kenai Lake, fiber from the Little Susitna, fiber from University Lake, fibers from Kepler Lake.Photo by Dyani Chapman | TPIN

It’s clear that the scope of plastic pollution in Southcentral Alaska is extensive. In order to address the environmental and waste crisis being caused by our overreliance on plastics, our leaders at the federal, state, local, and corporate levels should implement policies that will address this problem.

We offer the following recommendations:

Producer Responsibility

Producers are shifting the cost of their waste to consumers and taxpayers. Producer responsibility is a mechanism to shift the costs and management of postconsumer waste from local governments and consumers and onto producers themselves, requiring producers of plastic products to design, manage, and finance waste and recycling programs. The Alaska legislature should pass statewide producer responsibility laws as quickly as possible. Additionally, congress should pass federal measures to make these programs more widespread and shift the burden onto those who are creating the pollution.

Tackle Fast Fashion

To fight synthetic textile waste, retailers must stop sending overstock, unsold, and unused clothing to landfills and incinerators. State and local governments should pass laws preventing this practice so that clothing manufacturers and retailers stop producing more clothing than society needs and uses.

Choose Natural Fibers

Data from this survey and numerous other studies indicate that synthetic fibers are one of the most ubiquitous forms of microplastic pollution. Retailers and clothing manufacturers should move away from making products containing synthetic plastic fibers, which inevitably contribute to microplastic pollution. Plant and animal based fibers decompose more quickly and when they leach into the environment, there is some evidence they are digestible.

Phase out single-use plastics

Nothing society uses for a few minutes should be able to pollute our environment for hundreds of years. Congress, Alaska state officials, and municipalities should continue to pass laws that phase out unnecessary single-use plastics such as plastic take-out containers, bags, cutlery, and packaging (the largest source of plastic waste in the world). Cutting off the source of some of the most prevalent forms of plastic pollution will help curtail the tide of microplastics entering the environment. Right now, 16 municipalities in Alaska, including Anchorage, have some ban or limitation on plastic bags, but few limits exist on some of the other sources of single use plastics.

Halt policies that promote increased manufacture & incineration of plastic

Communities and legislators in Alaska should oppose proposals to permit bringing facilities online explicitly to make new plastics, or policies that will promote plastics incineration under the guise of “advanced” or “chemical recycling”. Incineration does not dispose of microplastics.

Support Reuse

Reusing items can reduce the quantity of plastic we produce and that contaminates our waterways. The state and municipalities can direct and assist reuse.

Support Repair

Repair is also essential to long term use. For example, most electronics contain plastic components; electronic-plastics make up about 5% of municipal waste. Those components make it challenging to safely reclaim and reuse the valuable minerals in the device, and most of the methods leave dangerous pollution behind. If individuals have plenty of options for repair for their electronics through strong Right to Repair laws, they can extend the life of their goods and minimize another source of plastic (and metal) pollution.

Improve Sport Fishing Gear

Alaska is a global hub for sport fishing, and lost or snagged fishing line is one of the sources of microplastic pollution found in Southcentral Alaska, especially in Kenai Lake, Tern Lake, and other heavily fished freshwater. Historically, horse hair, silk, and linen were regularly used for fishing. There are also some microbial polyesters that can be digested by bacteria in aquatic environments, and those are another viable alternative to long lasting plastic gear. Anglers, lawmakers, agencies, tackle manufacturers, and guides should work together to transition to better fishing line materials and reinforce skills to better steward fishing holes.

Minimize Loss of Commercial Fishing Gear

Alaska is also a global hub for commercial fishing, and lost gear is regularly found on Alaska shores and in Alaska marine environments. Public education, gear take back programs like the Copper River Watershed Project, introducing some biodegradable elements, and marine spatial management are some of the solutions to limit ghost fishing and lost gear. Elected officials should continue working with agencies, fishermen, and local communities to identify ways to reduce lost plastic gear and maximize repair and repurposing of gear when it’s damaged.

Clean-up

We’re spewing plastic into our environment at an alarming rate, and clean-up is a relatively insignificant action compared to turning off the tap, especially because at least some of that cleanup will return to the environment. That said, funding efforts and supporting programs for marine debris clean-up will help our oceans and marine wildlife. Federal legislation like the Don Young Veterans Advancing Conservation Act and other similar policies are worth pursuing.

Topics

Authors

Dyani Chapman

State Director, Alaska Environment Research & Policy Center

Dyani runs campaigns to promote clean air, clean water, and open spaces in Alaska. She lives in Anchorage and loves to hike, ski and cook yummy food.

Joi Gross

Sea Grant Fellow, Student UAS

Joi Gross grew up in Anchorage and is currently studying for her undergraduate degree at University of Alaska Southeast.

Find Out More

Refill, Return, Reimagine: Innovative Solutions to Reduce Wasteful Packaging

Truth in recycling

Plastic bag bans work