Strengthening protections for our coast’s best places

We’ve identified the California coast’s most amazing places. We should make sure they have the protections they need.

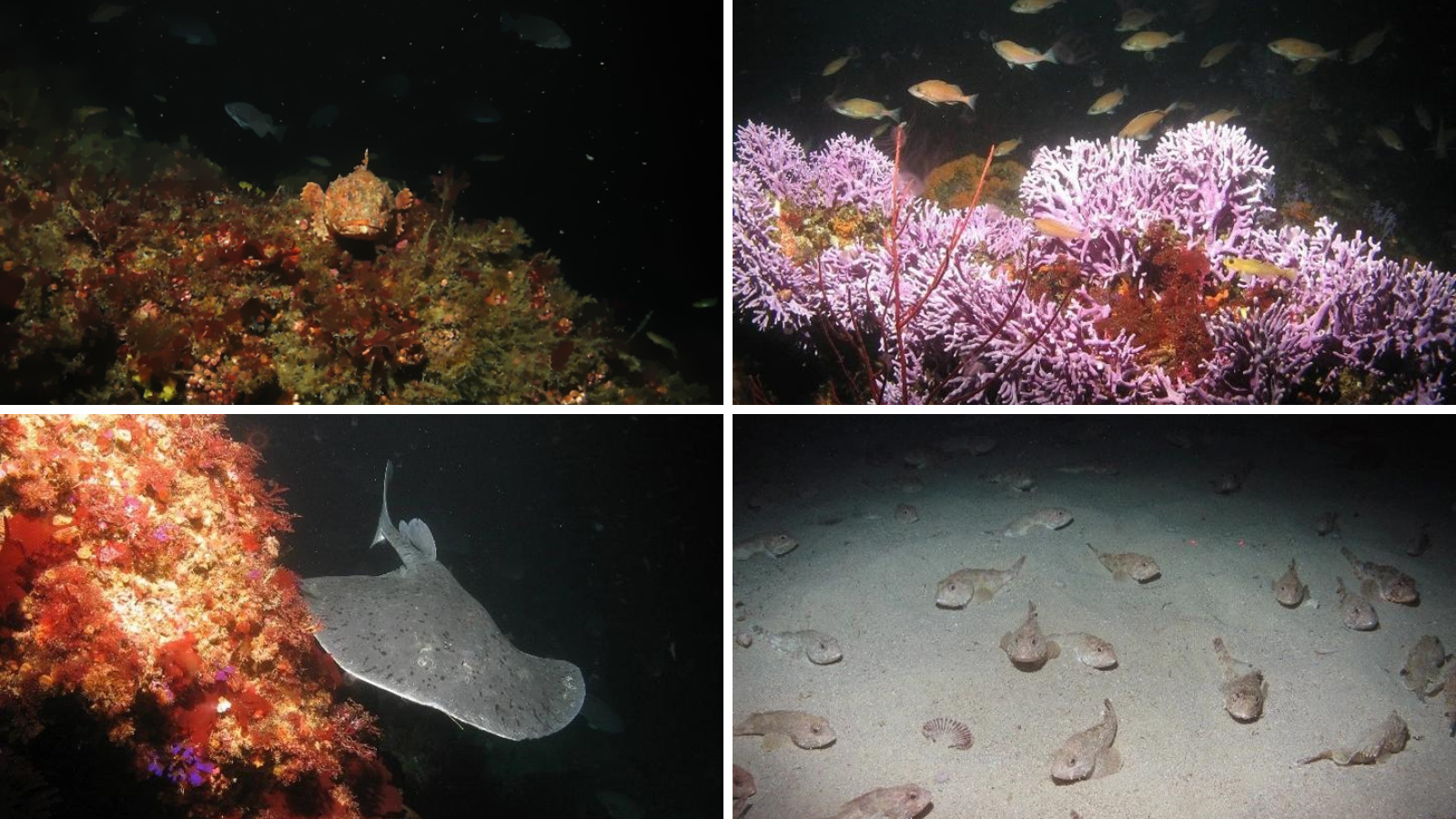

Located on the windward side of Santa Catalina Island, Farnsworth Bank, made up of a series of pinnacles and underwater mountains, hosts an underwater wonderland. Rare purple hydrocoral draws expert scuba divers and underwater photographers to the bank, while the shallow waters nearby host endangered black and white abalone

It’s no wonder Farnsworth Bank and its neighboring shoreline were slated for protection a decade ago as policymakers were assembling California’s groundbreaking system of ocean refuges or parks, called marine protected areas. This process created two different ocean parks in the area, Farnsworth Onshore State Marine Conservation Area and Farnsworth Offshore State Marine Conservation Area, intended to conserve Farnsworth’s unique ocean life for posterity.

Ten years on, it’s clear that even these well-intentioned and important protections may not be enough to keep Farnsworth Bank safe.

Why? The answer is simple: when they created these conservation areas a decade ago, policymakers tried to grandfather in a bunch of fishing activities that had a historical presence in the area, and which many hoped wouldn’t have too large an impact on the marine ecosystem in and around Farnsworth Bank. The result: the final conservation areas had long, confusing lists of rules that were almost impossible to understand, much less follow.

For example, here are the current regulations for Farnsworth Offshore State Marine Conservation Area:

It is unlawful to injure, damage, take, or possess any living, geological, or cultural marine resource, EXCEPT:

Recreational take of market squid by hand-held dip net; white seabass by spearfishing; pelagic finfish (northern anchovy, barracudas, billfishes, dorado (dolphinfish), Pacific herring, jack mackerel, Pacific mackerel, salmon, Pacific sardine, blue shark, salmon shark, shortfin mako shark, thresher shark, swordfish, tunas, Pacific bonito, and yellowtail) by hook-and-line or spearfishing, and marlin, tuna and dorado by trolling is allowed.

Commercial take of coastal pelagic species (northern anchovy, Pacific sardine, Pacific mackerel, jack mackerel, and market squid) by round-haul net, brail gear, and light boat; and swordfish by harpoon is allowed (no commercial take of marlin is allowed). Not more than five percent by weight of any commercial coastal pelagic species catch landed or possessed shall be other incidentally taken species.

This meant that the conservation areas created to protect Farnsworth Bank were (and still are) difficult to enforce. As highlighted during a 2020 forum the state hosted on compliance, rules are too complex, so that even law-abiding people on a recreational fishing trip may not know what kind of fishing, exactly, is allowed in the area they are fishing and what isn’t. And for state law enforcement officials trying to ensure everyone is following the rules, it was hard to distinguish between people doing legal types of recreational fishing and those doing similar, but illegal fishing.

This is a big problem for the ocean life at Farnsworth Bank: the protections designed to reduce harm to the area’s coral, abalone and fish couldn’t be relied upon to keep out harmful forms of fishing.

So if we want to protect Farnsworth Bank, for real, what should we do?

If we have decided that this place with its kaleidoscope of marine life, is worthy of protection for posterity, then we need to fix the rules. We need to make sure that people can understand that this place is a place for ocean life to thrive, where we humans are visitors and guests. And that means that the rules need to be clear, the types of allowed fishing easy to monitor.

That pretty straightforward solution was what we placed before California’s Fish and Game Commissioners in a recent proposal, which we submitted alongside another that would expand protections for California’s stable kelp forests. We called on the commissioners to strengthen protections around Farnsworth Bank and at Point Buchon, another critical habitat whose MPA designation has faced similar enforcement problems.

Our proposals would put in place far simpler and much stronger protections for these ocean areas. By making the rules stronger but simpler, we can be sure that these areas we’ve identified as special places can remain vital habitats for ocean life, while still allowing for people to scuba dive, photograph, spearfish and enjoy the Bank in ways that don’t pose a risk to its ecosystem.

Making the decision a decade ago to identify and protect its most important coastal habitats, California took the lead on ocean conservation, nationally and globally. But as the ocean changes and our understanding of how these protections work evolves, we need to ensure that we are adapting these once-groundbreaking marine protections to meet new challenges.

Our proposal, sitting now with the Fish and Game Commission, takes the first step towards addressing some of the gaps we can now see in the network. We hope it will spur state decisionmakers to take a step back and ask what they need to do to fill not only the gaps identified at Farnsworth Bank and Point Buchon, but also in other areas across the state.

Topics

Authors

Laura Deehan

State Director, Environment California Research & Policy Center

Laura directs Environment California’s work to tackle global warming, protect the ocean, and stand up for clean air, clean water and open spaces. Laura served on the Environment California board for two years before stepping into the state director role. Most recently, she directed the public health program for CALPIRG, another organization in The Public Interest Network, where she led campaigns to get lead out of school drinking water and toxic chemicals out of cosmetics. Prior to that, Laura ran Environment California citizen outreach offices across the state and, as the Environment California field director, she led campaigns to get California to go solar, ban single use plastic grocery bags, and go 100 percent renewable. Laura lives with her family in Richmond, California, where she enjoys hiking, yoga and baking.

Kelsey Lamp

Director, Protect Our Oceans Campaign, Environment America

Kelsey directs Environment America's national campaigns to protect our oceans. Kelsey lives in Boston, where she enjoys cooking, reading and exploring the city.

Rachel Lucine

Ocean Conservation Campaign Associate, Environment California

Rachel directs Environment California's campaigns to protect our oceans. She was an intern with Environment California for a year before joining staff full-time. Rachel works to protect and preserve the diverse species and habitats found off of California's coasts. Rachel lives in the Bay Area, where she enjoys reading, camping, hiking and learning new recipes.

Find Out More

California’s ocean life is threatened

Save sea otters, protect the ocean

A sea turtle tour to protect California’s coast