Electric vehicles are good. We can make them better.

There are many possible futures for electric vehicles - some of them better for the environment than others. Here are seven ways to make EVs even greener.

Imagine a world without pollution from vehicle tailpipes. A world in which inefficient, gas-guzzling cars and trucks are replaced with clean, hyper-efficient vehicles powered by electricity generated from the sun and the wind.

That world is no longer the future. It is here … if you look in the right places.

In Norway, roughly four out of five new vehicles sold are powered by batteries. In China, EVs make up a quarter of new cars sold, with the percentage rising fast. The U.S. is not moving quite as quickly – EVs accounted for only 6% of new vehicle sales in the U.S. in 2022 – but in California, zero-emission vehicles (including battery-electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fuel cell vehicles) now make up roughly 20% of light-duty vehicle sales, with the majority of those EVs. Indeed, the state has already hit its goal of putting 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles on the road two years early.

I got a taste of the EV future on a recent multi-city swing through California.[1] I showed up at a rental car counter and was surprisingly handed the key to a Tesla Model 3. The Tesla was efficient, responsive and sleek. Recharging the vehicle at Tesla’s Supercharger network was a snap and, while not exactly cheap, was less expensive than the alternative. It’s no wonder that the Tesla Model Y and Model 3 were the number 1 and number 2-selling vehicles in California last year.

The arrival of EVs is good news for the climate. Whether you believe (as I do) that there should be many fewer cars on the road, or that there should be two in every driveway, decarbonizing our transportation system will soon require that every car be powered by something other than oil. EVs not only make it possible to operate cars on zero-carbon energy, but, because they are more than four times as energy efficient as comparable gasoline-powered vehicles, they can also dramatically slash the total amount of energy we use for transportation.

Dig a little bit deeper, however, and it becomes clear that there is not just one possible future for electric vehicles. There are many. Some of those futures are far better for the environment, our health, and our quality of life than others.

A future in which all we do is electrify vehicles is likely to result in the world falling short in the effort to prevent the worst impacts of global warming. As I recently discussed with Somini Sengupta of the New York Times, electrifying transportation won’t reduce emissions fast enough or far enough to meet our nation’s climate goals. The state of California – America’s EV leader by a country mile – has determined that it must reduce the number of miles driven per capita by 25% by 2030 and 30% by 2045 to meet its climate goals. We need to integrate EVs into the transportation system in ways that complement existing low-carbon modes of travel such as transit, biking and walking, not compete with them.

Moreover, EVs are materials-intensive and current EV battery designs are reliant on the extraction of lithium and other so-called “critical minerals” that can cause tremendous damage to the environment and communities. At the same time, demand for electricity to power EVs increases the number of solar panels, wind turbines and other forms of renewable energy, along with transmission infrastructure, that we’ll need to build to support them, potentially exacerbating land-use conflicts that can either slow the clean energy transition or cause lasting harm to the natural environment.

America needs to move quickly to put electric vehicles on the road and phase out gasoline- and diesel-powered ones. But we also need policies that encourage us to maximize the environmental benefits of EVs.

Seven steps to a better EV future

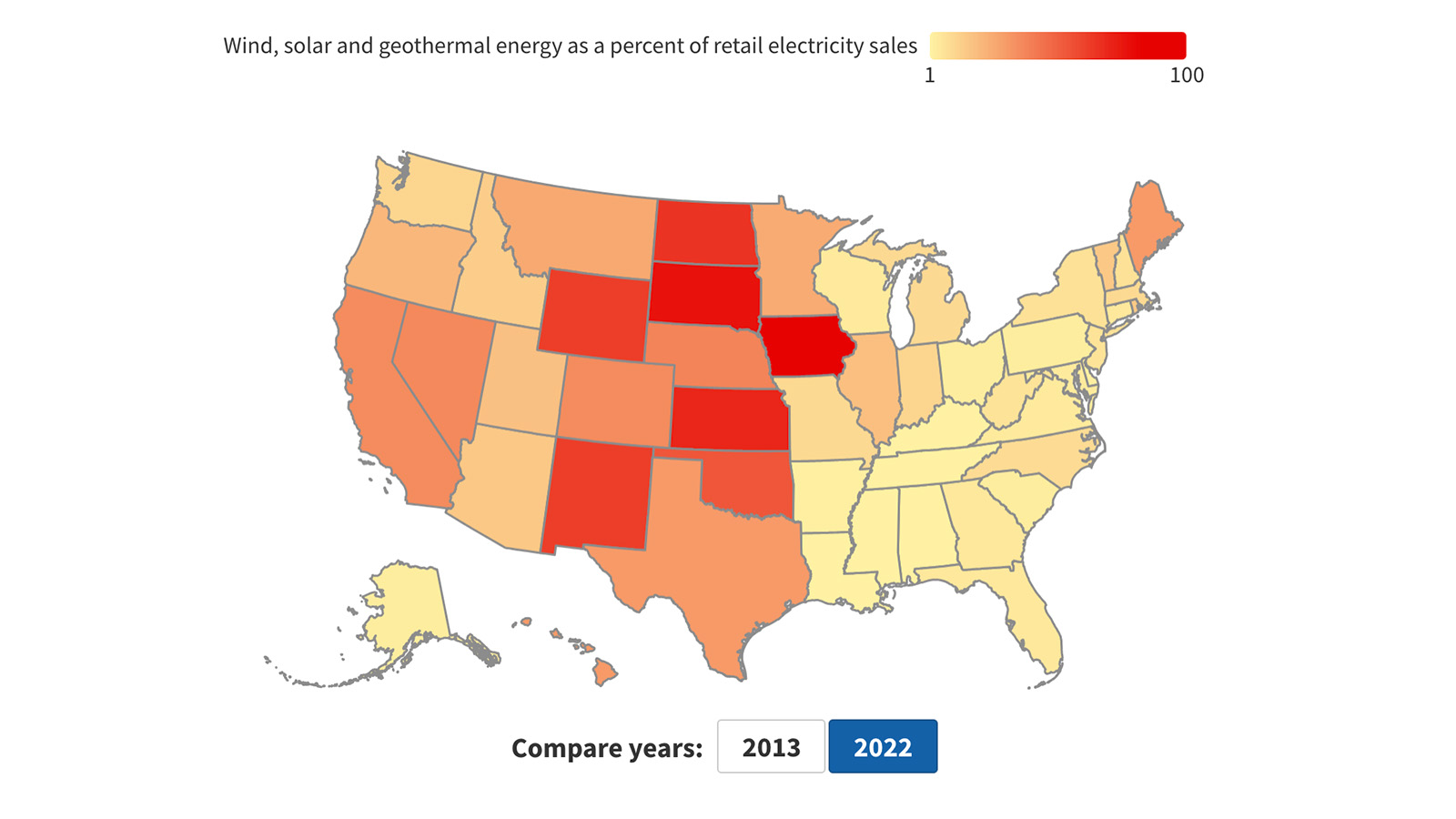

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, more than 90 percent of Americans live in parts of the United States where the average EV produces lower emissions than the most efficient gasoline car on the market. That number will only grow with time as the nation continues to shift from coal and other fossil fuels to renewable sources for electricity generation.

But there is a wide gap between the environmental performance of the best EVs and the worst ones. There is also a wide spread in the environmental impact of the same EV used in different ways.

Here are seven steps we can take to move toward a cleaner and healthier EV future.

1. Encourage smaller cars

When it comes to energy use, not all EVs are created equal.

The electric Hyundai Ioniq 6 sedan travels the equivalent of 140 miles per gallon of gasoline (24 kWh/100 mi.) as rated by the EPA, making it one of the most energy efficient EVs on the market. At the other end of the spectrum, the “wildly inefficient” GMC Hummer clocks in at a gluttonous 47 miles per gallon equivalent – a roughly three-fold difference in the number of miles that can be traveled on a given amount of power.

Recent research suggests that size is the top factor determining the efficiency of an EV. The electricity-sipping Ioniq 6 weighs in at 4,200 to 4,440 pounds curb weight, while the Hummer stands at a beefy 9,640 pounds.

An EV fleet that looks more like the Ioniq 6 and less like the Hummer would use one-third as much electricity – that’s a lot of wind turbines and transmission lines. Replacing travel in cars with travel by light-weight electric vehicles like e-bikes – which are roughly 10 times more efficient than electric cars — would go even further.

2) Encourage smaller batteries

This item is related to #1 because batteries are a significant share of the overall weight of an EV — for the aforementioned Hummer, the battery pack is nearly a third of the weight of the vehicle. But battery size matters for another reason as well: embodied greenhouse gas emissions.

Building an EV is more carbon-intensive than building an internal combustion engine vehicle due to emissions produced in the process of manufacturing the batteries. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, EVs begin generating net emission savings after 12,000 to 21,000 miles of driving, with the average EV reducing lifetime emissions by more than 50 percent compared with the average gasoline-powered car (and more, of course, in places where the grid is cleaner.)

Emissions from battery manufacturing vary based on where the batteries are made, and also by their size, with larger batteries being more emissions-intensive to manufacture than smaller ones.

In recent years, automakers have moved toward bigger and bigger batteries in their EVs, with the median range of an EV now at 257 miles, as opposed to just 90 miles in model year 2015. With the average American driver traveling only about 40 miles each day, much of that battery capacity remains unused most of the time. Moving toward appropriately sized batteries – supported by more ubiquitous and convenient public charging – could reduce the amount of energy needed for battery production.

3) Encourage slower travel

Gasoline-powered vehicles achieve their maximum fuel efficiency in the range of 30 to 60 miles per hour. For EVs, though, the picture is different. If you’ve ever looked at the fuel economy sticker of an EV, you may have noticed that mileage in the city is actually higher than mileage on the highway. That’s partly because city driving allows EVs to recapture energy through regenerative braking and partly because the efficiency of EVs declines pretty much linearly with speed (with the exception of the energy needed to heat or cool the cabin). The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that electric vehicles are 77 to 79 percent efficient at translating energy from electricity to motion in highway driving, but can achieve efficiencies of 94 percent or more in stop-and-go city driving.

According to one estimate, the optimal speed for maximizing the fuel economy of an EV is in the teens during moderate weather. Does that mean we should all drive 10 miles an hour? Or replace every highway off-ramp with a traffic light to create more stop-and-go driving? Not necessarily. But it does mean that moderating speed is almost always a good idea for saving energy.

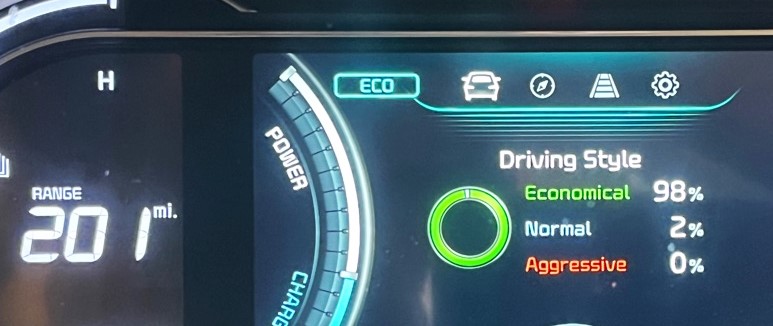

4) Encourage energy-efficient driving modes

Electric vehicles allow drivers a great deal of control over vehicle performance. Our family’s new-ish EV comes with multiple settings that can be adjusted to maximize range and fuel economy. First there are the driving modes – Eco, Normal and Sport – that affect vehicle performance. Then there are the settings for the strength of the vehicle’s regenerative braking system, which allow you to choose whether you want the car to behave like a traditional vehicle and coast to a stop, or to maximize the amount of energy recaptured and sent back to the battery when decelerating.

How much difference do these settings make to fuel economy? It is hard to get a straight answer, and much depends on the vehicle and the type of driving being done, but energy savings from regenerative braking can be significant. Creating incentives to use more energy-efficient modes – beyond the inherent incentive that comes from extending a vehicle’s driving range – can help maximize the amount of energy per mile.

5) Encourage slower and off-peak charging

If much of the greenhouse gas emissions of an EV come from the manufacture of the battery, then it stands to reason that getting the longest and best possible life out of a battery is a key strategy for reducing its lifetime environmental impact. Frequent reliance on fast charging can degrade a battery’s ability to hold a charge over time, though the effect does not appear to be dramatic in modern EVs. An additional issue is that the higher power demand of fast chargers – as well as additional demand from any kind of EV charging at times of peak electricity use – can increase strain on the grid, potentially leading to continued use of gas power plants. By charging slowly, we can reduce strain on the electricity system, and by charging at times when clean energy on the grid is abundant, we can reduce emissions as well.

6) Encourage recycling and second-life uses of batteries

In their landmark study on strategies for reducing lithium demand from electric vehicles, the Climate and Communities Project estimated that recycling could cut lithium demand (in a scenario with less personal car ownership and smaller batteries) by as much as half. But recycling may not even be the best immediate option for batteries that can no longer hold enough charge to reliably power a car. Used EV batteries can be a relatively inexpensive and reliable source of additional energy storage capacity for the grid – helping us to speed the transition to clean, affordable renewable energy. In either case, vehicles and batteries should be designed to allow for repair, reuse and recycling – and “circular economy” supply chains established to ensure that society gets the maximum value out of every battery we make.

7) Encourage sharing of vehicles and rides

America’s model of personal car ownership, and our patterns of solo driving, are remarkably inefficient uses of energy and resources. Electric vehicles – whether cars, buses or trains – will do a more efficient and effective job of moving people when they are more fully occupied. And sharing vehicles can reduce the number we need to manufacture in the first place.

How can we make electric vehicles even better for the environment?

With transportation now America’s number 1 source of greenhouse gas emissions, the stakes involved in successfully making the leap to electric vehicles are high. So are the stakes of making that transition in the best way possible. We cannot afford to leave it to chance – we need public policy.

The good news is that some of the tools to encourage a sustainable EV transition already exist. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s upcoming proposal of new Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards creates one opportunity to nudge the EV transition toward more efficient vehicle models. Other changes – expanding access to charging, expanding clean public transportation, reducing vehicle speeds – involve infrastructure policies. Still other changes – such as encouraging more efficient modes of travel in EVs and ride sharing – may require entirely new policy templates.

But the benefits of combining the transition to EVs with other supportive policies can be massive. The Climate and Community Project analysis found that combining efforts to reduce automobile dependence with policies to reduce vehicle size and encourage recycling could reduce lithium demand by as much as 90%. The findings echo our own conclusions in our 2016 report “A New Way Forward,” which found that a strategy that combined electrification with efforts to improve vehicle efficiency and reduce vehicle travel could reduce energy demand from urban light-duty vehicles by 89 to 91%. Such a reduction would make the other challenges posed by the clean energy transition – from access to raw materials to environmental and land use conflicts – that much more manageable. And many of the suggestions above – smaller vehicles, lower speeds, more shared trips – have the potential to make our streets safer for all users as well.

Let me be clear: Even if we do it in a less-than-optimal way, the transition to electric vehicles is an essential strategy to address climate change. Every fossil fuel-powered vehicle that hits the road from now on moves us that much farther away from our climate goals. Nor can the transition to EVs be taken for granted – the fossil fuel industry and the makers of internal combustion engine vehicles remain among the most powerful special interests in the world. They are not going away, and we can’t underestimate the power of the status quo and special interests to keep us dependent on inherently climate-wrecking technologies and fuels for transportation.

But the transition to EVs creates another opportunity to reset the conversation about how Americans travel, and to reimagine what our transportation system can be. By embracing the EV transition and working hard to make it better, we can ensure that, unlike our current transportation system, the EV future we build truly protects our health, environment and quality of life.

[1] Yes, I know, I drove. Connecting four mid-sized cities/suburbs via transit in California turns out to be quite a feat. Hopefully by the time of my next visit, there will be more and better options.

Topics

Find Out More

Renewables On The Rise Dashboard

Electric Vehicles Save Money for Government Fleets