Rough Waters Ahead

The Impact of the Trump Administration's EPA Budget Cuts on Montana's Waterways

With the dedicated work of local, state, and federal governments - along with residents - the long process of restoring Montana's waterways to health is underway. Now, because of deep and devastating proposed cuts to the EPA, that progress is now in jeopardy.

Downloads

Montana’s waterways are critical to the health and welfare of our families, our communities, and wildlife.

Montana’s natural beauty hides major challenges facing our waterways. Fish and other aquatic wildlife struggle to survive in some of our rivers and streams, not all residents have safe water to drink, and mining wastes pollute many of the state’s waterways. But, with the dedicated work of local, state and federal governments – along with residents – the long process of restoring Montana’s waterways to health is underway.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been essential to those efforts – supporting and working with state and local officials and residents to keep pollution out of our waterways, hold polluters accountable, restore degraded waterways to health, and study and monitor Montana’s waterways to ensure their future health and safety.

That progress is now in jeopardy. The Trump administration has proposed deep and devastating cuts to the EPA’s budget. Even if the president’s proposed cuts are scaled back by Congress, they would still have profound negative impacts on the agency’s ability to deter pollution from mines, oil spills, logging, sewage treatment plants, runoff and other sources, while undercutting efforts to restore lakes, rivers and streams across Montana.

We need a strong EPA with sufficient resources to support local cleanup efforts and to partner with state government and communities to protect and restore Montana’s waterways.

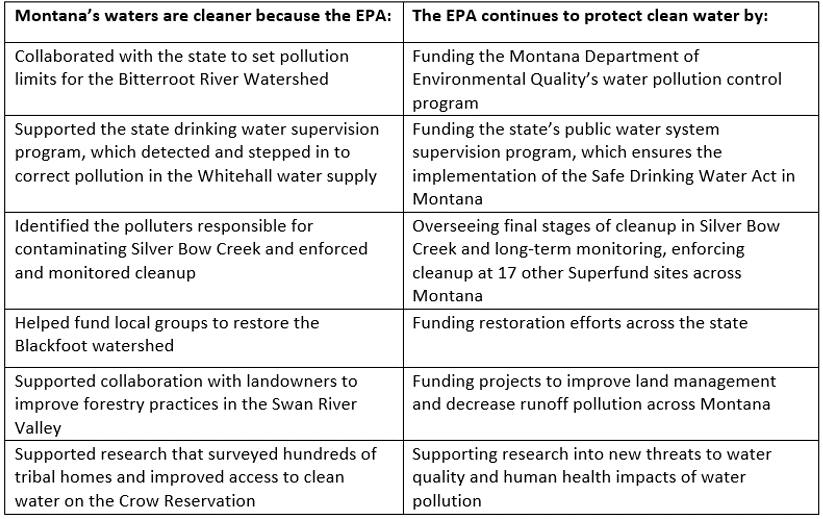

Montana’s lakes, rivers and streams are being protected and restored with funding and effort from the EPA. The EPA has worked to:

- Keep pollution out of our waterways: The Bitterroot River is the third-most heavily fished trout river in Montana. Angling interest in the Bitterroot has, in part, resulted from efforts to counteract historic water pollution issues, such as sediment, nutrient loading, elevated temperature, and metal pollution.[1] The Montana Department of Environmental Quality and the EPA have collaborated since 2003 to set pollution limits to restore the Bitterroot watershed.[2] As a result of these limits and extensive restoration efforts, the Bitterroot watershed is now on the path to recovery. For example, Meadow Creek, a stream in the headwaters of the Bitterroot River that could not support aquatic life due to sediment pollution and damage caused by overgrazing, had so improved by 2016 that the state no longer classified it as impaired. It now offers healthy habitat for aquatic life.[3]

- Hold polluters accountable: Nearly a century of mining and smelting contaminated Silver Bow Creek with heavy metals, rendering the water so toxic that the creek had no fish.[4] In 1983, the EPA designated the Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area on the upper Clark Fork as a Superfund site, and the agency has enforced and overseen the creek’s cleanup by Atlantic Richfield Company and 25 other polluters.[5] Work has included removing contaminated tailings, reforming a natural channel in the creek, and restoring riparian and aquatic habitat, all of which has returned a wild and native trout fishery to Silver Bow Creek.[6] The EPA continues to oversee the final stages of cleanup and long-term monitoring of the area.

- Restore waterways to health: Logging and grazing in the Swan River Valley dumped sediment into the valley’s creeks, threatening native bull trout populations.[7] The Montana Department of Environmental Quality used EPA funding to support Swan Valley Connections’ work to help educate local landowners about forestry practices such as buffer zones that counter erosion and protect bull trout.[8] Swan Valley Connections’ close collaboration with landowners across the Swan Valley cut sediment loading by at least a third, resulting in better river conditions.[9] The Montana Department of Environmental Quality recently received additional EPA funding to remove old bridge abutments and collaborate with the U.S. Forest Service to study additional options to reduce runoff from logging roads.[10]

- Conduct research and educate the public: Researchers at Little Big Horn College and Montana State University who received EPA funding surveyed water quality in hundreds of homes on the Crow Reservation, finding metal, nitrate and bacteria contamination from polluted groundwater and streams in more than half of homes tested.[11] The research team’s findings allowed members of the Crow tribe to better understand drinking water threats and to obtain tools to protect public health, such as water coolers and home filtration systems.[12]

Table ES-1. How Clean Water in Montana Depends on the EPA

The Trump administration’s proposed cuts to the EPA budget put these and other critical programs in danger – threatening the future health of Montana’s waterways.

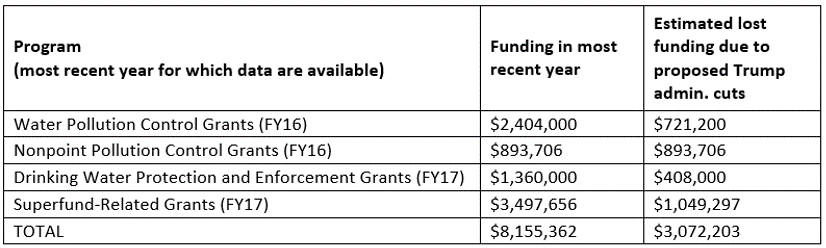

- Many federal grants from the EPA to state governments for clean water would be slashed by 30 percent or more – making it more difficult for already cash-strapped state agencies to do their jobs and delaying important locally led cleanup efforts.[13] For example, the proposed budget would end grants to state governments and tribal agencies to address pollution from farms, stormwater runoff and other dispersed sources.[14]

- Research and development funding would be cut by 47 percent, limiting support for scientists, residents and local communities trying to understand the ever-changing threats facing their waterways.[15] For instance, the EPA’s Safe and Sustainable Water Resources research program, which supports science and technology research to protect drinking water, would be cut by more than a third.

- Funding for EPA’s Superfund cleanup program would be reduced by 30 percent, slowing progress on existing cleanup sites and preventing new cleanups from being added.[16]

- Overall, the EPA budget would be reduced by 31 percent.[17]

Even if Congress makes some of these budget cuts less drastic, Montana’s waterways will still suffer without full funding of EPA programs.

Table ES-2. Estimated EPA Grant Funding Losses to Montana if Trump Administration’s Proposed Budget Is Enacted (table shows selected programs[18]

Note: Estimates are calculated assuming EPA budget cuts affect all states by the same percentage. Reductions are based on grants from most recent fiscal year.

The job of cleaning up and protecting Montana’s streams, river and lakes is not done. Only a well-funded EPA can continue the region’s legacy of progress in cleaning up Montana’s waterways and ensure that they are healthy and safe for us and future generations to enjoy.

[1] Big Sky Fishing, Fly Fishing the Bitterroot River, accessed 6 August 2017 at http://www.bigskyfishing.com/River-Fishing/SW-MT-Rivers/bitterroot-river… Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Final – Bitterroot Watershed Total Maximum Daily Loads and Water Quality Improvement Plan, December 2014, accessed 6 August 2017 at http://deq.mt.gov/Portals/112/Water/WQPB/TMDL/PDF/Bitterroot/C05-TMDL-04….

[2] Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Completed TMDLs in the Bitterroot River Watershed, accessed 6 August 2017 at http://montanatmdlflathead.pbworks.com/w/page/55313043/Completed%20TMDLs%20in%20the%20Bitterroot%20River%20Watershed.

[3] Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Mapping DEQ’s Data, accessed 6 August 2017 at http://svc.mt.gov/deq/wmadst/default.aspx?requestor=DST&type=CWAIC&CycleYear=2016.

[4] Jim Robbins, “Butte Breaks New Ground to Mop Up a World-Class Mess,” New York Times, 21 July 1998, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170801210044/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/21/science/butte-breaks-new-ground-to-mop-up-a-world-class-mess.html.

[5] Butte Citizens Technical Environmental Committee, Who Cleans Up a Superfund Site, accessed 7 July 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170707144754/http://www.buttectec.org/?page_id=37, and Montana Department of Justice, Silver Bow Creek Update: Remediation & Restoration of Silver Bow Creek (factsheet), June 2011, accessed 1 August 2017 at https://web.archive.org/web/20170801210243/https://dojmt.gov/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/silverbowcreekfactsheet.pdf.

[6] Montana Department of Justice, Silver Bow Creek Update: Remediation & Restoration of Silver Bow Creek (factsheet), June 2011, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170801210243/https://dojmt.gov/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/silverbowcreekfactsheet.pdf, and Susan Dunlap, “Can You Eat the Fish in Silver Bow Creek?,” Montana Standard, 30 March 2015, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170801211134/http://mtstandard.com/news/local/can-you-eat-the-fish-in-silver-bow-creek/article_696ce0ee-9cbf-5f39-9981-d2370aab6cc1.html.

[7] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Section 319 Nonpoint Source Program Success Story: Forest Best Management Practices Improve Water Quality, November 2015, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170706024331/https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-11/documents/mt_piper_goat.pdf.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Robert Ray, Montana Department of Environmental Quality, personal communication, 22 August 2017.

[11] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Water, Our Voice to the Future: Climate Change Adaptation and Waterborne Disease Prevention on the Crow Reservation, accessed 5 September 2017 at https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.highlight/abstract/10252/report/0, and Brian Bienkowski, “Tainted Water Imperils Health, Traditions for Montana Tribe,” Environmental Health News, 22 August 2016, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170707023147/http://www.environmentalhealthnews.org/ehs/news/2016/tribal-series/crow-series/crow-health-water-justice-part1.

[12] John T. Doyle, Margaret J. Eggers, Anne K. Camper and the Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee, Water, Our Voice to the Future: Climate Change Adaptation and Waterborne Disease Prevention on the Crow Reservation (powerpoint at 2016 EPA Tribal Progress Review Meeting), October 2010, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170707022237/https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-10/documents/4b_doyle_eggers_camper_lbh.pdf.

[13] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, FY 2018 EPA Budget in Brief, May 2017, 43.

[14] Ibid, p. 39.

[15] Office of Management and Budget, Appendix: Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, 2017.

[16] See note 13, p. 38.

[17] Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness, Fiscal Year 2018, 2017.

[18] Estimated losses to individual states are based on the assumption that EPA budget cuts will affect all states by the same percentage. That percentage cut was applied to grant funding for each state in the most recent fiscal year for which data were available. “Water Pollution Control Grants” are Section 106 grants, slated for a 30 percent cut. “Nonpoint Pollution Control Grants” are Section 319 grants, cut entirely in the administration’s proposed budget. “Drinking Water Protection and Enforcement Grants” are Public Water System Supervision grants, cut by 30 percent. “Superfund-Related Grants” includes all grants with Superfund in their program title. Information on proposed cuts comes from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, FY 2018 EPA Budget in Brief, May 2017, 38, 39 and 43. Lost funding by state is based on most recent funding levels for each program: FY 2016 for Section 106, per U.S. EPA, FINAL Section 106 FY 2016 Funding Targets with Rescission, 29 December 2015, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170727210615/https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-04/documents/final_fy_16_section_106_with_rescission_standard.pdf. FY 2016 for Section 319, per U.S. EPA, Grants Reporting and Tracking System, accessed 18 August 2017, at https://ofmpub.epa.gov/apex/grts/f?p=109:9118:::NO:::. FY 2017 for PWSS grants, per Memorandum from Anita M. Thompson, Director, Drinking Water Protection Division, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, to Regional Drinking Water Programs Managers, Final Allotments for the FY 2017 Public Water System Supervision (PWSS) State and Tribal Support Grants, 30 May 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170727210933/https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-06/documents/wsg_202_pwss_fy17_allotments.pdf. FY 2017 for Superfund-related grants, per www.usaspending.gov, accessed 14 September 2017.