Victory for the Great American Outdoors

For what would become the nation’s most effective conservation and recreation law, it was an awkward beginning.

For what would become the nation’s most effective conservation and recreation law, it was an awkward beginning.

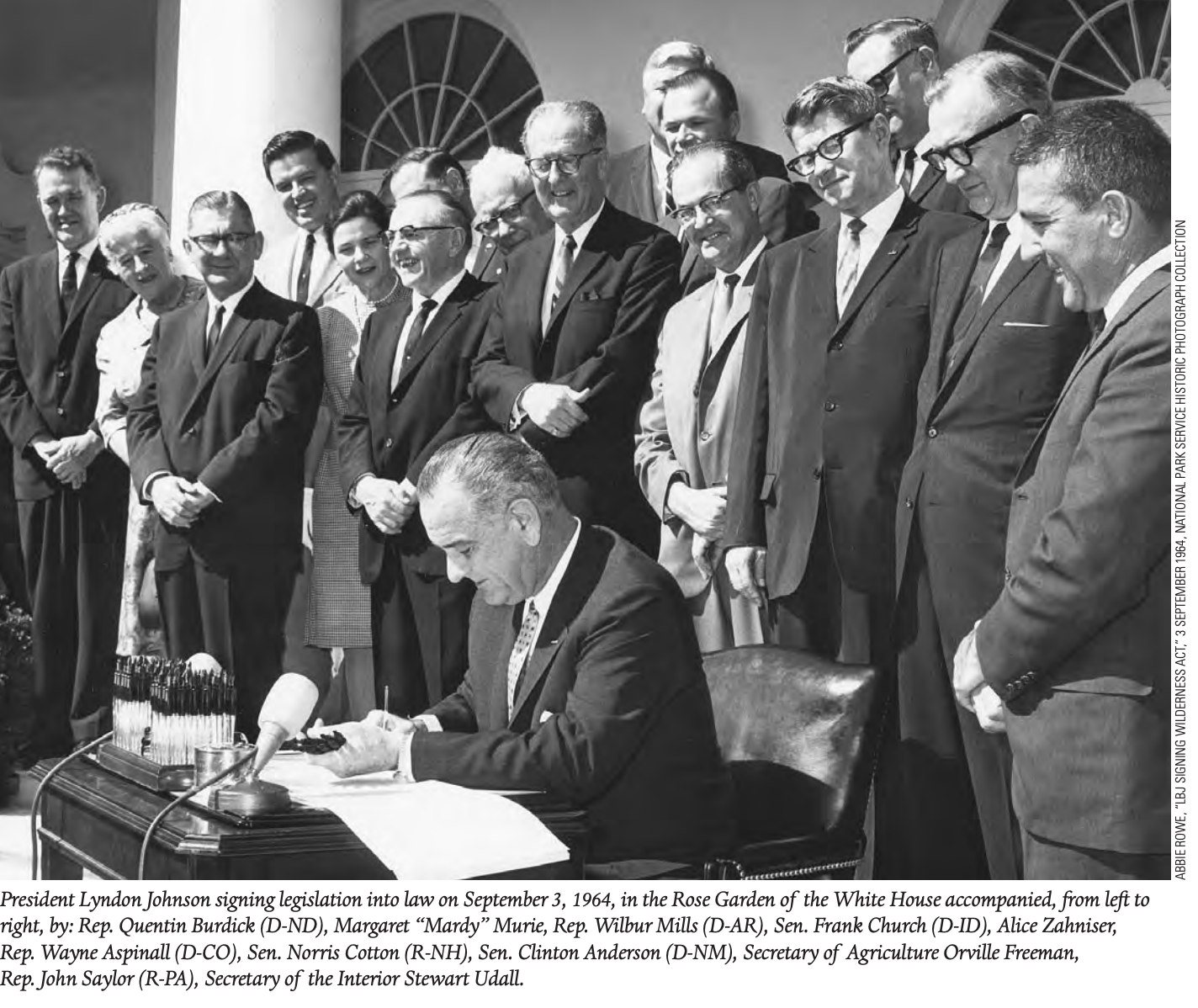

Cabinet secretaries, senators, representatives and other leaders had gathered to witness President Johnson sign two conservation bills into law: The Wilderness Act and the Land and Water Conservation Fund. As the president signed the wilderness bill into law, the dignitaries smiled for the cameras as they stood closely around the president.

By the time President Johnson signed the second bill, the Land and Water Conservation Fund bill, the attention span of the VIPs was … elsewhere.

And that’s the way it’s been over the past 50 years for the LWCF: unheralded at the start, little-known by the general public, and almost always underfunded by Congress.

Yet the program has quietly but effectively gotten the job done, “preserving, developing, and assuring accessibility to all citizens” for outdoor recreation by putting billions of federal dollars into national parks, places of cultural and historic value, and local parks, playgrounds and playing fields. Add it all up and America has gotten more than 15 million acres of public land conserved in almost every single county in the country. For example:

- Where can you find some natural scenery in Metro Atlanta? Along the Chatahoochee River National Recreation Area, protected by the LWCF.

- Where can you learn about the battle to end school segregation? In Topeka, Kansas, at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, preserved by the LWCF.

- How has California managed to create or improve more than 1,000 parks since 1965? Yep: The LWCF.

- As recently as 2010, Environment America and the state environmental groups ran successful campaigns to put the Land and Water Conservation Fund to work expanding Mount Rainier National Park and forestalling development within Acadia National Park, among other places.

Americans were promised more

So what’s the problem? Why has Environment America had to run a campaign to save and fund the LWCF for the past two years?

For one thing, no matter how effective the LWCF has been, it’s hard to keep up with the breakneck pace of development in the U.S. Every year in America, new roads, houses, pipelines and other development replace natural areas that, if you put them all together, would be larger than the state of Rhode Island

For another, Americans were promised more. Much more.

The LWCF was supposed to serve as a trust fund, with the money raised primarily in the form of royalties paid by oil companies for offshore drilling leases — up to $900 million per year — and then held and spent on behalf of all Americans to ensure our access to outdoor recreation.

Except it hasn’t worked that way. Since 1965, Congress has fully funded the program just twice (in 1998 and 2001), diverting more than $22 billion for other purposes. To put that figure into perspective, as of 2019 the program had provided $18 billion for conservation projects. If Congress had upheld the original promise of the LWCF, the program could have preserved, protected, improved or created far more of America’s best places — perhaps double the amount of land and water.

If undermining the program’s funding and failing to fulfill its promise wasn’t bad enough, Congress let the program expire in September 2018.

Working in coalition with The Wilderness Society, National Wildlife Federation and others, we sought to clean up this mess in two ways: by permanently reauthorizing the program and securing the full $900 million per year for it for … well, forever.

Strategy for success

To achieve these goals, Conservation Director Steve Blackledge and his team needed to: weave together the local and national elements of the Land and Water Conservation Fund success story; break out of the progressive v. conservative narrative that frames virtually all policies these days; and demonstrate strong grassroots support for the program “back home” — in the states and districts represented by the members of Congress whose backing would be decisive.

Here’s how we carried out this three-part strategy:

- In the fall of 2018, we called on then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who had been a strong LWCF supporter when he served in Congress, to help save the program. Staff and volunteers blanketed Washington, D.C., businesses and neighborhoods — including Secretary Zinke’s — with lawn signs urging him to stand up for LWCF.

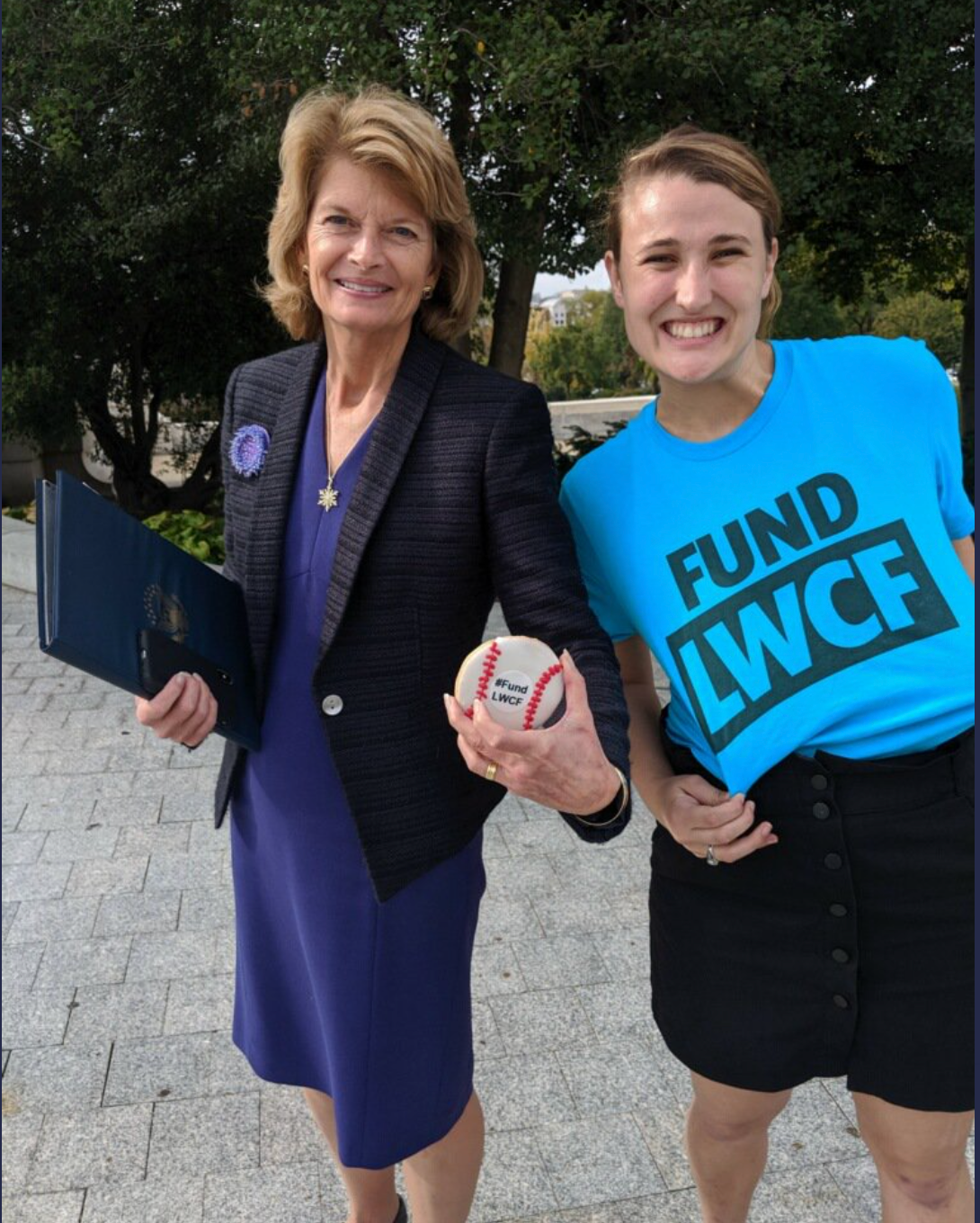

- Our advocates partnered with members of Congress and local officials in states such as West Virginia, Nevada, New Mexico, Missouri and South Carolina to draft op-eds for local newspapers and to hold events aimed at highlighting our congressional allies’ work and the places that need our protection. This work earned shout-outs from Sen. Maria Cantwell (Wash.) and Rep. Diana DeGette (Colo.), among others.

- With organizers spreading out across the country in August 2019 and beyond, we gathered photo petitions from people featuring pictures of some of the iconic places LWCF protects, and we reached out to our members and supporters, who graciously allowed us to place more than a thousand lawn signs in key states.

By late February 2019, we had won our first big victory. With a strong, bipartisan majority, both houses of Congress passed a bill to reauthorize LWCF permanently, and the president signed it into law that March.

Yet there was still nothing to stop Congress from continuing to divert LWCF funds elsewhere. Entering a new fiscal year, President Trump even proposed a budget that would have slashed its funding by 97 percent. We needed to guarantee that LWCF would be fully funded — permanently.

A breakthrough

Then, we had a breakthrough: In February 2020, when a reporter asked Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell what Congress could accomplish amid all the partisan gridlock, he singled out LWCF as a strong possibility.

Now, if we’re being honest, it’s possible that Leader McConnell’s motives were in part political. Two members of his caucus — Sens. Cory Gardner (Colo.) and Steve Daines (Mont.) — face tough races in the upcoming 2020 election. Passage of a big land conservation bill could help their chances. The vehicle for this gambit became the Great American Outdoors Act, which not only promised LWCF full and permanent funding, but also funded a backlog of long-overdue maintenance projects on our public lands.

The fact that this bill had political overtones might have given us pause if we were a partisan group, but we’re not. We’re an environmental group. So we backed it.

To push the Great American Outdoors Act over the finish line in the Senate, we planned a major day of action in Washington, D.C. When the COVID-19 crisis made that impossible, we switched most meetings to phone: Our advocates held 55 remote meetings and calls with key congressional staff to rally support for the bill.

Our members and supporters also sent tens of thousands of messages to Congress in support of LWCF over the years, including more than 11,000 during the final push to pass the Great American Outdoors Act.

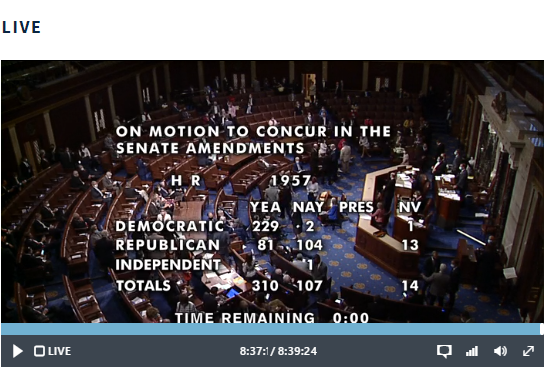

On June 17, that work paid off with another big, bipartisan victory, by a vote of 73-25, in the Senate. Weeks after we organized a virtual rally featuring six members of Congress, the House followed suit on July 22, in a 310-107 vote. We expect (with fingers crossed) the president to sign the bill into law.

The little law that could is now a lot bigger

Fifty-five years after President Johnson signed the bill that created the program, the Land and Water Conservation Fund still doesn’t get all of the recognition it deserves. But thanks to the work and support of our staff, members, partners and allies, the program is in a stronger position than ever to preserve the land and waters we love for all Americans to explore and enjoy.

Topics

Authors

Steve Blackledge

Senior Director, Conservation America Campaign, Environment America

Steve directs Environment America’s efforts to protect our public lands and waters and the species that depend on them. He led our successful campaign to win full and permanent funding for our nation’s best conservation and recreation program, the Land and Water Conservation Fund. He previously oversaw U.S. PIRG’s public health campaigns. Steve lives in Sacramento, California, with his family, where he enjoys biking and exploring Northern California.

Find Out More

EPA report says pesticides endanger wildlife

Why we should save the bees, especially the wild bees who need our help most

Why Alaska’s NPR-A, site of the Willow Project, deserves protection