Catelyn Toney

Clean Water Intern

Texas is number one for water pollution, with slaughterhouses major contributor

Clean Water Intern

Executive Director, Environment Texas Research & Policy Center

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed in January new rules to limit water pollution by meat and poultry products (MPP) plants, a major source of water pollution in Texas.

For many years, Texas has held the title as one of the worst water polluters in the nation, ranking #1 for toxic substances in 2022. Last year, meat and poultry plants discharged 24 million pounds of dissolved solids, 1.8 million pounds of nitrogen, and 241,000 pounds of phosphorus into Texas waterways.

Direct and indirect pollution of rivers, lakes, and streams from slaughterhouses is a problem for many reasons including:

The EPA’s proposal responds to a lawsuit where Environment America, Earthjustice, Environmental Integrity Project, and other organizations sued the EPA for failing to adhere to the Clean Water Act. While the Clean Water Act requires the EPA to set and review water pollution standards for the slaughterhouse industry every year, the EPA failed to update effluent (liquid waste/pollution) regulations for large meat and poultry plants since 2004.

The EPA has proposed three different approaches to reducing slaughterhouse pollution. The first option, preferred by the EPA, includes new phosphorus and revised nitrogen limits, along with new pretreatment standards on certain pollutants for large or direct dischargers. Though this plan is predicted to reduce national nitrogen and phosphorus pollution by about 100 million pounds per year, it doesn’t apply nutrient limits to MPP plants that send their wastewater to municipal treatment facilities.

The second and third options in the proposal suggest stronger limits than option 1 and would hold both direct and indirect dischargers accountable, with the third option covering the greatest number of polluting facilities and reducing pollution by about 332 million pounds per year.

Key Differences Between Proposed Options for MPP Water Pollution Limitations

| EPA Proposed Option | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 |

| Overall Pollution Reduction (lbs. per year) | 100 million | 288 million | 322 million |

| Nutrient Pollution Reduction | 15% | 54% | 85% |

| People Affected within 1 mile of MPP discharge | 1.3 million | 8.9 million | 22.1 million |

| Facilities Covered | 22% | 22% | 42% |

Option 1 of the EPA’s proposal would allow large MPP facilities to continue indirectly polluting by sending the problem and cost to water treatment facilities that then dump their treated water directly into lakes, rivers and streams. We have seen the adverse effects of this in the Gulf of Mexico and waterways that feed into it. Water treatment is often insufficient at ridding water of industrial pollutants that “are more difficult to remove from water” because they lack advanced techniques and technology. This is a key area where Option 3 outperforms Option 1.

Option 3 regulates nitrogen and phosphorus from facilities that send their wastewater to sewage treatment plants (called indirect dischargers). While one might think the sewage plants clean up this pollution before releasing wastewater to our rivers, EPA’s own analysis (pg. 4480) found otherwise: 73% of the sewage treatment plants receiving slaughterhouse pollution reviewed by the EPA had permit violations for pollutants found in the industry’s wastewater – including nitrogen and phosphorus. And the problem is even worse because a majority of these sewage plants do not even have pollution limits for these nutrients.

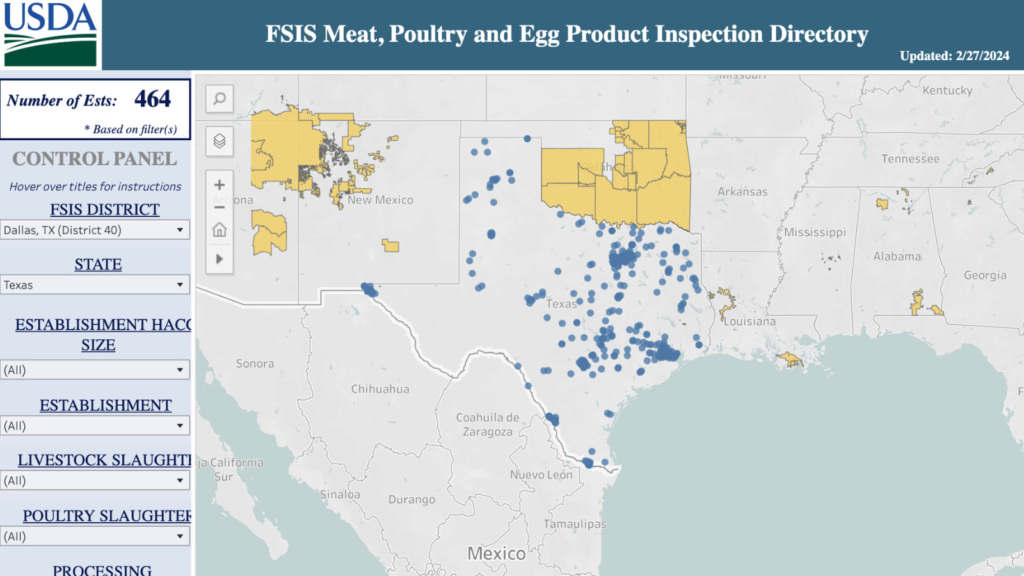

One of Texas’ major MPP polluters, as deemed by EPA, is a Tyson Farms facility located in Shelby (between La Grange and Brenham), near the Huana Creek watershed. In 2021, 98.4% of the chemicals that this business disposed of were nitrate compounds. Additionally, according to Environment America’s 2022 analysis of toxic water pollution, Pilgrim’s Pride in Mount Pleasant (northeast Texas) polluted Tankersley Creek with about 1.7 million pounds of nitrate compounds. Not only did this affect nearby ecosystems, but also Lake O’ the Pines which Tankersley Creek flows into. These are just two examples of the 468 total MPP plants in Texas.

Map of all meat, poultry, and egg product facilities recorded by the United States Department of Agriculture.Photo by USDA | Public Domain

Both the federal and state governments try to limit and regulate water pollution by subjecting slaughterhouses and other food production facilities to a permitting process. Other strategies to limit water pollution should be more widely instituted including reduced excess fertilizer application, cover crops, buffer zones, and frequent equipment safety and environmental inspections.

Members of the public have responded to the proposal via online comments and public hearings that took place January 24 and January 31, 2024. The next hearing will happen on March 20, 2024.

The EPA must reach a final decision on this proposed rule by August 2025, in accordance with the consent decree. You can urge the agency to adopt the most stringent limitations on both direct and indirect MPP polluters. Comments are due March 25th, 2024.

While we acknowledge and appreciate the EPA’s steps to finally improve effluent limitations/guidelines, we must not allow polluters — big or small, direct or indirect — to continue contaminating Texas waterways. Texans need and deserve clean water. It is central to living a healthy and enjoyable life. It’s time to let the EPA know that Texans demand consistent analysis and better regulation to ensure these water systems remain protected and pure.

Clean Water Intern

Catelyn is an intern at Environment Texas and student at the University of Texas at Austin. She is studying biology and hopes to work in environmental conservation.

As the director of Environment Texas, Luke is a leading voice in the state for clean air, clean water, clean energy and open space. Luke has led successful campaigns to win permanent protection for the Christmas Mountains of Big Bend; to compel Exxon, Shell and Chevron Phillips to cut air pollution at three Texas refineries and chemical plants; and to boost funding for water conservation and state parks. The San Antonio Current has called Luke "long one of the most energetic and dedicated defenders of environmental issues in the state." He has been named one of the "Top Lobbyists for Causes" by Capitol Inside, received the President's Award from the Texas Recreation and Parks Society for his work to protect Texas parks, and was chosen for the inaugural class of "Next Generation Fellows" by the Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law at UT Austin. Luke, his wife, son and daughter are working to visit every state park in Texas.