Wasting our Waterways

Toxic pollution and the unfulfilled promise of the Clean Water Act

Polluters poured nearly 200 million pounds of toxic substances into U.S. waterways in 2020. We must strengthen Clean Water Act protections and reduce toxics use.

Download the report

Fifty years ago, our nation came together to pass the federal Clean Water Act, with an ambitious goal of making all of America’s waterways clean. Heralding a new era for America’s rivers, lakes and streams, the Clean Water Act led to dramatic reductions in pollution and to the restoration of several waterways.

But a half-century later, the job of cleaning up America’s waterways remains half-done. Many of our waterways still face major pollution threats – including industrial facilities that continue to release large volumes of toxic substances, threatening the health of people and ecosystems.

According to data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), industrial facilities released at least 193.6 million pounds of toxic substances into U.S. waterways in 2020, including chemicals known to cause cancer, reproductive problems and developmental issues in children. These high volumes stand in stark contrast to the Clean Water Act’s stated objective of eliminating direct discharges of pollution by 1985.

To end this toxic threat to America’s waterways, our nation should:

- reduce the use of toxic chemicals;

- update pollution control standards; and

- strengthen Clean Water Act protections and enforcement.

Industrial facilities dump toxics into waterways nationwide.

Our analysis examined this toxic water pollution reported to TRI in 2020 from several vantage points.

Toxics in our waters

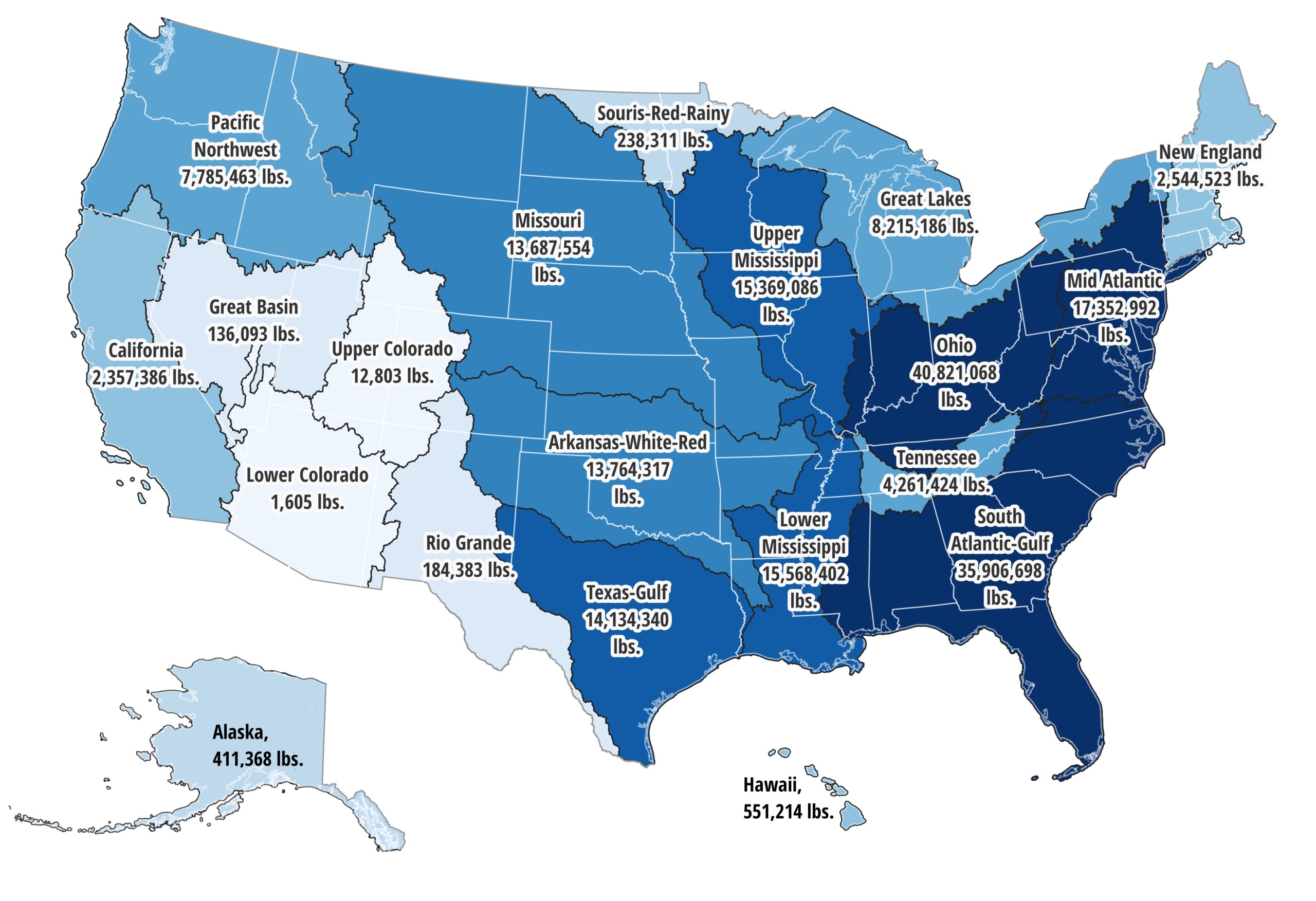

Which watersheds received the most toxic releases?

Industrial and government facilities released toxic substances into 844 local watersheds nationwide – representing about one in every three local watersheds in the U.S. These five local watersheds received the largest amounts of toxic chemical discharges by weight in 2020:

Top five local watersheds by toxic substances released, 2020

| Receiving watershed | State(s) containing watershed | Toxics released (lbs.) |

| Lower Ohio-Little Pigeon | IN, KY | 12,008,366 |

| Upper New | NC, TN, VA | 10,266,141 |

| Brandywine-Christina | DE, MD, PA | 6,191,362 |

| Lower Cape Fear | NC | 5,017,810 |

| Muskingum | OH | 4,640,523 |

Among major watershed regions nationwide, the Ohio River basin received the largest volume of toxic discharges by weight in 2020, followed by the South Atlantic-Gulf, and Mid-Atlantic watershed regions.

See our full report for a list of the 50 local watersheds where polluters dumped the most toxic substances.

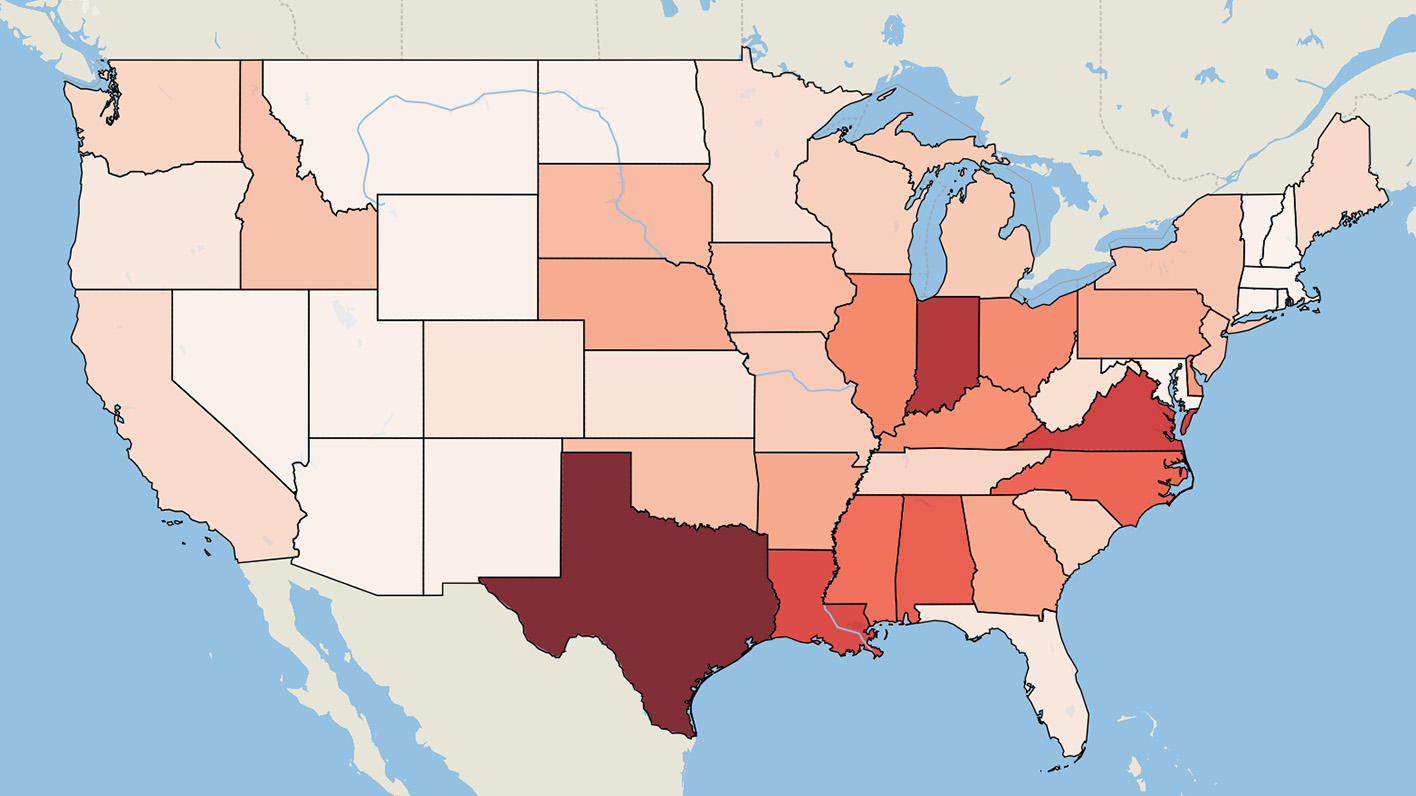

Which states allowed polluters to dump the largest volume of toxic substances?

Texas, Indiana and Virginia ranked highest in the nation for toxic chemical discharges to water by weight in 2020.

Top five states by toxic substances released in 2020

| State or territory | Toxics released (lbs.) |

| Texas | 16,778,747 |

| Indiana | 14,085,748 |

| Virginia | 12,218,174 |

| Louisiana | 11,378,399 |

| Alabama | 10,173,322 |

See our full report for the volume and toxicity of releases in all U.S. states and territories.

Where did polluters release substances with the greatest potential threats to human health?

Some waterways received particularly large discharges of chemicals with potent effects on human health.

- Wisconsin, Texas and Virginia were the three states with the largest toxicity-weighted releases of chemicals by industrial and government facilities in 2020.

- The Ohio River, Great Lakes and Texas-Gulf watershed regions had the largest releases of chemicals weighted by toxicity.

What are key health risks of this pollution?

Many chemicals discharged into American waterways have been linked to severe health problems.

- Cancer: Just over 1 million pounds of toxic chemicals linked to cancer were released to waterways across America in 2020. More cancer-causing chemicals were released into the waters of South Carolina, Texas and Alabama than any other states in 2020, and the Austin-Oyster watershed in Texas, the Cooper watershed in South Carolina, and the Racoon-Symmes watershed in Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia received the most cancer-causing toxics among local watersheds. The industries that released the most cancer-causing toxics were paper and pulp mills.

- Reproductive effects: Over 200,000 pounds of chemicals that potentially cause reproductive problems were released in 2020, with Texas, Indiana and Pennsylvania waterways receiving the greatest amount of reproductive toxics. The Middle Wabash-Little Vermilion watershed in Illinois and Indiana ranked first with more than 13,000 pounds of chemical releases tied to reproductive toxicity, followed by the Lehigh watershed in Pennsylvania and the Upper San Antonio watershed in Texas. The industries that discharged the most reproductive toxics into water were fossil fuel power plants and iron and steel mills.

- Developmental effects: Over 4.5 million pounds of chemicals with the potential to affect the healthy development of fetuses and children were released into American waterways in 2020. North Carolina, Wisconsin and Alabama were the states with the largest releases of developmental toxics, with the Castle Rock watershed in Wisconsin, the Middle Neuse watershed in North Carolina and the Lower Alabama watershed in Alabama receiving the greatest amount of developmental toxic releases. Pulp, paper and paperboard mills were the largest releasers of developmental toxics.

What pollutant was dumped in the highest volume and why does it matter?

Nitrate compounds accounted for more than 90% of all toxic releases by weight, with animal processing plants and petroleum refiners representing the largest sources of nitrates. Nitrates are not only dangerous to human health, but they also contribute to the formation of oxygen-depleted “dead zones” in waterways such as the Gulf of Mexico that harm wildlife.

Which industries are pouring this pollution into our waterways?

- When measured by toxicity, the industries with the greatest releases to waterways include chemical and plastics manufacturing, refineries, fossil fuel power plants, and metals.

- Meat and poultry processing are among the industries with the highest volume (pounds) of toxic releases

- Well-known companies own or operate many of the facilities with the most significant toxic releases in each state.

You can find detailed listings of toxic releases by industry, facility, and parent company in Appendices B and C of our full report.

What about forever chemicals?

Releases of a small number of “forever chemicals” known as PFAS were reported to the Toxics Release Inventory for the first time in 2020, though the true volume of PFAS releases is likely much higher.

- For the first time in 2020, industrial polluters were required to report their releases of certain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – chemicals that have been linked to kidney cancer, thyroid disruption and other health problems. PFAS are toxic at extremely low doses – health advocates have recommended limits on PFAS in drinking water of 1 part per trillion, equivalent to just one drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools – and PFAS chemicals persist in the environment over time.

- Industrial polluters reported releasing at least 440 pounds of PFAS to waterways in 2020. However, given that the 2020 TRI reporting only included 172 out of more than 12,000 types of PFAS, and likely omits many facilities that use or release PFAS, this figure likely dramatically understates the amount of PFAS pollution. The EPA is currently planning to update TRI reporting rules and pollution control standards for at least some industries discharging PFAS to waterways.

How can we stop this toxic pollution of our waterways?

To further the promise of the Clean Water Act, and to protect our rivers, lakes, streams and bays from toxic pollution, policymakers should take the following actions:

- The EPA should move quickly to update pollution control standards in order to end or at least dramatically reduce toxic releases into our waterways. This includes standards for meat and poultry processing plants, power plants, and all industrial dischargers of PFAS chemicals.

- Officials should require industrial facilities to remove toxics from the wastewater they send to sewage treatment plants (otherwise known as publicly owned treatment works, or POTWs) that are unable to be removed by those plants and may be discharged into waterways. These “indirect discharges” of industrial toxic chemicals are significant and have the potential to affect the environment and health.

- The EPA should eliminate the de minimis exemption for PFAS chemicals, which likely results in PFAS releases being underreported to TRI. Similarly, Congress and the EPA should continue to expand the scope of reporting to TRI and ensure that reports of toxic releases under the program are complete and accurate.

- Federal and state officials, as well as product manufacturers, should dramatically restrict the use of PFAS and other toxic chemicals, especially where safer alternatives already exist.

- EPA and state officials should ensure that facilities that use or store large quantities of toxic material are not permitted near our waterways, reducing the threat of large-scale spills of toxics into waterways that cause immediate and long-term harm.

- Congress should provide the EPA with sufficient funding to ensure rigorous and timely review and vigorous enforcement of water pollution permits.

- State and federal officials should ratchet down toxic pollution limits in clean water permits, especially where a facility is discharging into a waterway already polluted with toxic substances.

- The federal government should confirm that all of America’s wetlands, streams and other waters are protected from toxic pollution by the Clean Water Act.

- State and federal officials should move beyond voluntary incentives to dramatically curb the flow of toxic pollutants from non-point sources, especially runoff of nitrates and pesticides from industrial agribusiness operations.

About the data in this report

The EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) is the nation’s most comprehensive source of data on the release of specific toxic substances to waterways. However, TRI data captures only a portion of the toxic pollution released to waterways by industrial facilities, meaning that the amount of toxic substances released to waterways by industrial facilities is likely significantly higher than reported here. Among the releases excluded from TRI reporting are the following:

- Releases from industries exempt from reporting. Oil and gas extraction, for example, have historically been exempt from reporting under TRI (though reporting for natural gas processing facilities will be required starting in 2023).

- Releases of toxic substances that have not yet been added to the list of reportable chemicals. (For example, reporting for releases of some PFAS was only required as recently as 2020, and is still not required for the vast majority of these “forever chemicals.”)

- Releases from facilities with fewer than 10 full-time employees or that do not meet minimum thresholds for the amount of a substance manufactured, processed or otherwise used at a facility.

- Releases that fall under various other exemptions in the law, such as the de minimis exemption that allows facilities to avoid counting some chemicals present in low concentrations in products when determining whether they are required to report under the law.

Topics

Authors

Matt Casale

Former Director, Environment Campaigns, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Bryn Huxley-Reicher

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Find Out More

Good intentions, bad outcomes. Six ways impervious surfaces harm our cities and the environment

Safe for Swimming?

The Threat of “Forever Chemicals”